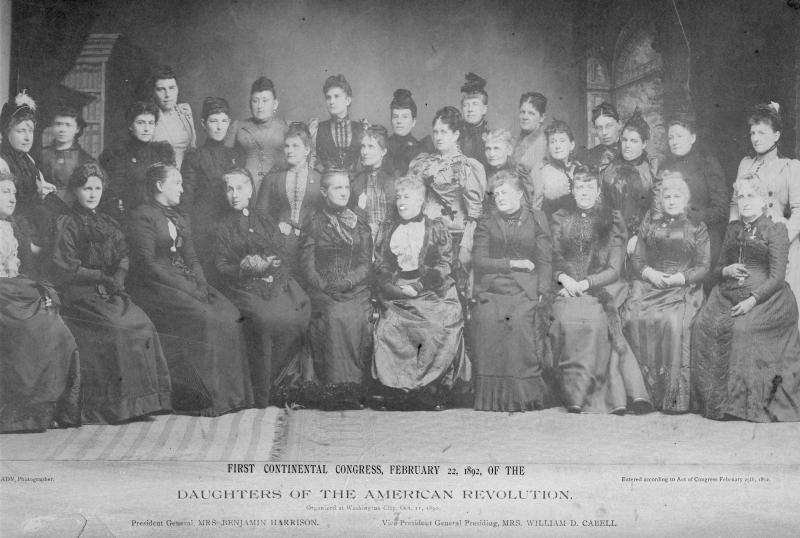

All Daughters of the American Revolution are descended from Revolutionary War patriots and soldiers. Imagine, though, joining the DAR through the Revolutionary War service of your own father. This was the distinct privilege of a Real Daughter. Not to be confused with the “daughter of a Revolutionary war soldier or patriot,” a Real Daughter was distinguished because she was a DAR member as well as the actual daughter of a soldier or patriot. In the early years of the National Society, a DAR chapter who could name one or more of the 767 Real Daughters among its members was extremely proud of this living link to the American Revolution.

The goal of this online exhibition is to celebrate the lives and accomplishments of this very special group of women. It tells the story of the Real Daughters Committee formed during the DAR’s early days for the purpose of encouraging Real Daughters to join the DAR and to care for those who needed assistance. This exhibition highlights the stories of some of the most interesting Real Daughters.

If you are interested in learning more about Real Daughters, you can purchase the book, My Father Was a Solider, from the DAR store.

A Living Link

At one of the first organizational meetings of the Daughters of the American Revolution one of the many topics discussed was the interesting fact that there were several widows and at least two daughters of Revolutionary War soldiers living. The names of twenty-three widows still on the United States pension list were read and seemed an impressive number to many at the meeting. It is unlikely, therefore, that anyone during the first days of the Society guessed how many daughters of American patriots actually were still alive. At Continental Congress in 1895, a Miss Laws from Ohio reported on a “true Daughter” in the Cincinnati Chapter and stated “there are less than a dozen in the whole country.” The total number of daughters of Revolutionary patriots enrolled in the DAR, however, would eventually climb to more than 700. As stated in the article “Born to Greatness: The Daughters of the First Patriots” in the September/October 2007 edition of American Spirit magazine, many of these women “were the youngest daughters of a large family or the result of a marriage late in life.”

A Living Link

The earliest years of the DAR were occupied with the details of administration, organization and solidifying the Constitution and By-laws of the Society. But as these issues were gradually settled, officers and members could reflect on what had occurred in the Society during its formative years. They realized the steadily growing number of Real Daughters within their ranks. By the late 1890s, National Officers reported regularly on the statistics of these ladies. In her report at Congress in 1896, Recording Secretary General Lyla Buchanan said:

The several patriotic societies have brought into prominence the names of numbers of veritable sons and daughters of Revolutionary patriots. I have prepared from our records a list of our Daughters of Revolutionary patriots, members of this Society, numbering 69. Twenty are credited to Connecticut, some of whom have reached the remarkable age of four score years and fourteen. All honor to these revered members of our Society.

Encouraged by the knowledge that there were more Real Daughters to be found, DAR chapters began actively to seek them out. The Joseph Habersham Chapter in Georgia was the most successful, eventually counting 31 Real Daughters as members of the chapter. The chapter’s founder, Lucy Cook Peel (pictured here), wrote an advertisement for The Atlanta Constitution newspaper in order to recruit daughters of Revolutionary War soldiers. They received responses from as far away as Texas and Virginia. The state of Massachusetts included more Real Daughters than any other state society with 120, followed closely by Connecticut with 106 and New York with 91. The Report of the Daughters of the American Revolution to the Smithsonian in 1900–1901 presented a “catalogue” of Real Daughters which then equaled 551.

A Living Link

DAR chapters treasured their Real Daughters. Several chapters, without direction from a state society or the National Society, created “pensions” for Real Daughters living in poverty. In some cases these pensions were a Real Daughter’s only source of income. Upon hearing this disturbing news, many officers and members of the National Society also took up the cause of supporting these overlooked women and began petitioning the United States government to provide pensions for Real Daughters. At the Ninth Continental Congress in 1900, Corresponding Secretary General Kate Kearney Henry read the names of seven Real Daughters who were to receive U.S. pensions, but questioned “why the rest are not entitled to the same bounty at the hands of this Government.” While many DAR members continued their efforts to persuade government officials to secure more pensions for Real Daughters, there was never a comprehensive federal ruling. But the DAR persisted in collecting money for its own contributions. During her final report at Congress in 1901, Mrs. Henry again broached the subject of pensions, stating:

I need not now recite the familiar history of the failure of the effort to have the country at large care for these last links that join us to the glorious past. I wish to recommend and advise that each State shall take up the subject and secure the future of its own “Real Daughters.” That seems to me now the only practicable method of performing, what may, I think, be called a sacred duty of our organization.

Later during Congress of the same year, Laura Wentworth Fowler, the Chapter Regent of the Old South Chapter, offered another resolution “authorizing the Treasurer of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution to appropriate money for the support of those ‘Real Daughters’ who are in need.” This resolution passed.

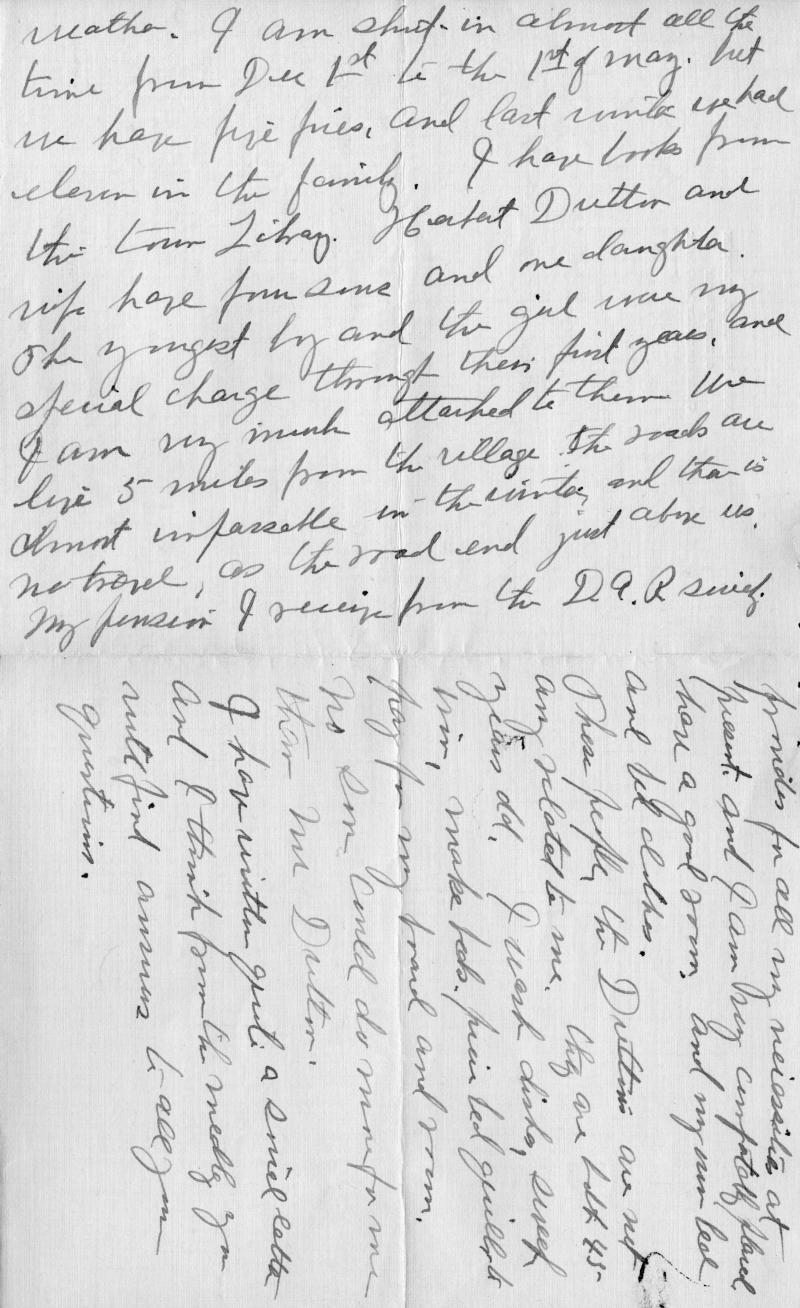

Real Daughter Caroline Randall wrote to the National Society several times. In this 1926 letter (pictured here) she discusses the DAR’s monetary contributions, saying, “My pension I receive from the D.A.R. society provides for all my necessities at present and I am very comfortably placed.”

A Living Link

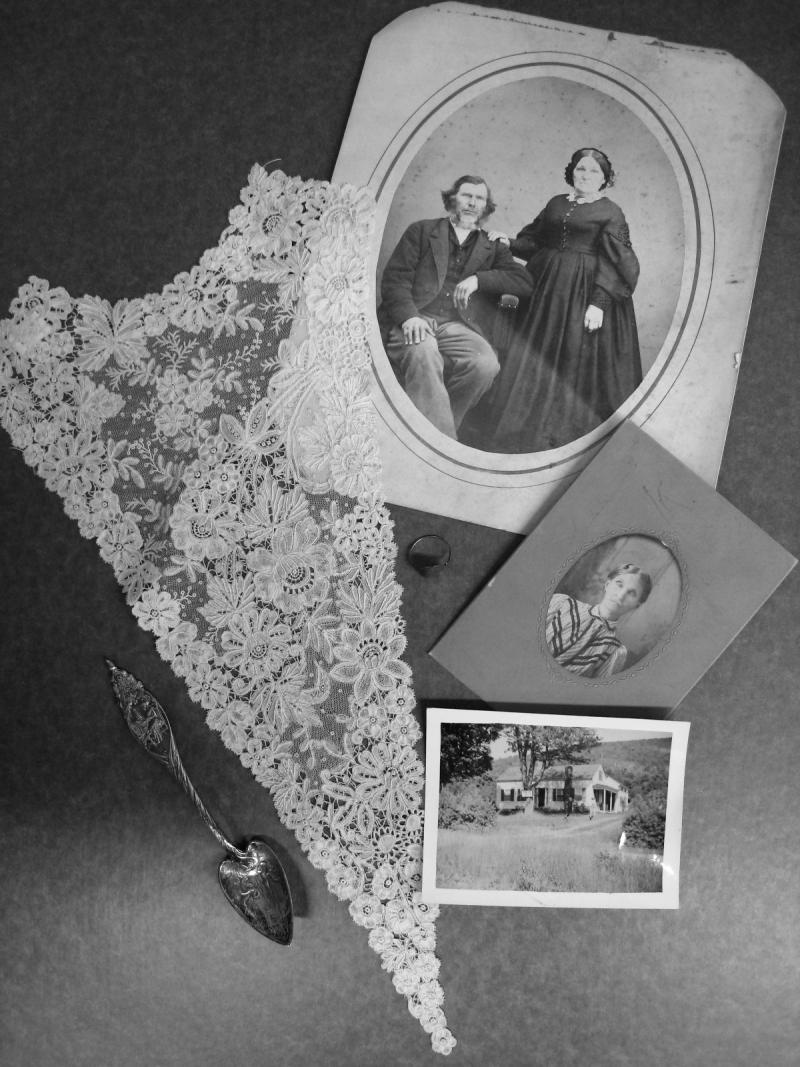

At Congress in 1895, the State Regent of New Jersey, a Mrs. Shippen, proposed the idea of presenting each Real Daughter with a souvenir spoon as a gift from the National Society. They decided to use the Official Souvenir Spoon already being produced with added personalized engravings in order to honor each individual Real Daughter. Every “Real Daughter spoon” was engraved with the daughter’s initials on the back of the handle along with the message “Presented by the National Society DAR” on the bowl. The Real Daughter’s National Number was often engraved on the back of the handle as well. The Official Souvenir Spoon of the National Society was made by J.E. Caldwell, the official jeweler of the DAR. It was sold as a souvenir and fundraiser and was intended for purchase by any DAR member. The design features a woman sitting at a spinning wheel on the handle’s tip, with flax running down the length of the handle and spread into the letters “DAR” on the bowl of the spoon. The top of the handle also has 13 stars for the original Colonies and a banner with DAR’s motto at the time “Home & Country.” The spoons were available in a tea spoon size and a smaller coffee spoon size. They were made of sterling silver, but could also be purchased with a golden gilt overlay on the bowl or over the entire spoon. These souvenir spoons initially sold for between $1.50 and $3.

A Living Link

Mary Jane Seymour was one of the DAR National Officers who realized the unique opportunity to collect information, artifacts and photographs from Real Daughters. Mrs. Seymour grew interested in the Real Daughters, who she called “the most interesting wards of our Society,” while working on the verification of their applications as Registrar General (1896–1897). Later, as Historian General (1898–1900), she began requesting stories about their fathers and their own lives. Much like the oral histories collected today, she wanted to preserve these individual histories that are so important to understanding the broader history of America. Mrs. Seymour placed these letters, memoirs and photographs in a scrapbook which she later donated to the Society in a presentation at Continental Congress. Several other items given by the Real Daughters to the Committee on Revolutionary Relics later became part of the DAR Museum collections or the NSDAR Archives collections.

A Living Link

During a meeting of the National Board of Management in January 1903, the Board decided to form a committee devoted solely to processing the applications of Real Daughters. Several daughters of Revolutionary patriots died while waiting for the verification of their papers and had never officially been accepted into the Society. Through a resolution presented by Margaret B. Harvey, the DAR vowed to place the names of these women “upon the role of honor,” but this did not make up for the lost opportunity of including them in the National Society. The new committee worked to ensure every potential Real Daughter’s application was reviewed in a timely manner.

Eventually, the Committee on Real Daughters or, later, the Real Daughters Committee, took control of all matters concerning the Real Daughters. They began recording the names of women who had received spoons and kept track of those who needed pensions. Members of the Real Daughters Committee often made regular visits to local Real Daughters, bringing gifts or news of the Society. They celebrated birthdays, mourned deaths, provided companionship and made the Real Daughters feel important and special. This committee existed until 1943 after the death of the last Real Daughter, Annie Knight Gregory. This “National Chairman of the Real Daughters Committee” pin pictured here belonged to Helen Newberry Joy.

A Living Link

The National Historical Magazine reported on the death of Caroline Randall in 1942 and noted that the time between the birth of her father and her death was 177 years. In her book Real Daughters of the American Revolution, published in 1912, Margaret B. Harvey wrote that “fully 25 or more reached the century mark; while so many passed their ninetieth birthday that anything less seems like youth.”

The Real Daughters are not only fascinating for living long lives through the beginning years of our country or because of their Revolutionary fathers, but because they also encourage an understanding of the youth and originality of the United States. The knowledge that the combined life spans of a father and daughter could reach as far back as the American Revolution and go through the beginning of World War II is remarkable. Ultimately, the Real Daughters were honored by the DAR because they were “living links” and active participants in America’s history.

Pictured here members of the Real Daughters Committee, Helen Coe Hammond (left) and Grace A. Coe (right) of the Nova Caesarea Chapter in New Jersey, visited Real Daughter Caroline Randall (center) on June 15, 1938. Miss Coe’s memoir of the trip is part of the Real Daughters collection in the NSDAR Archives.

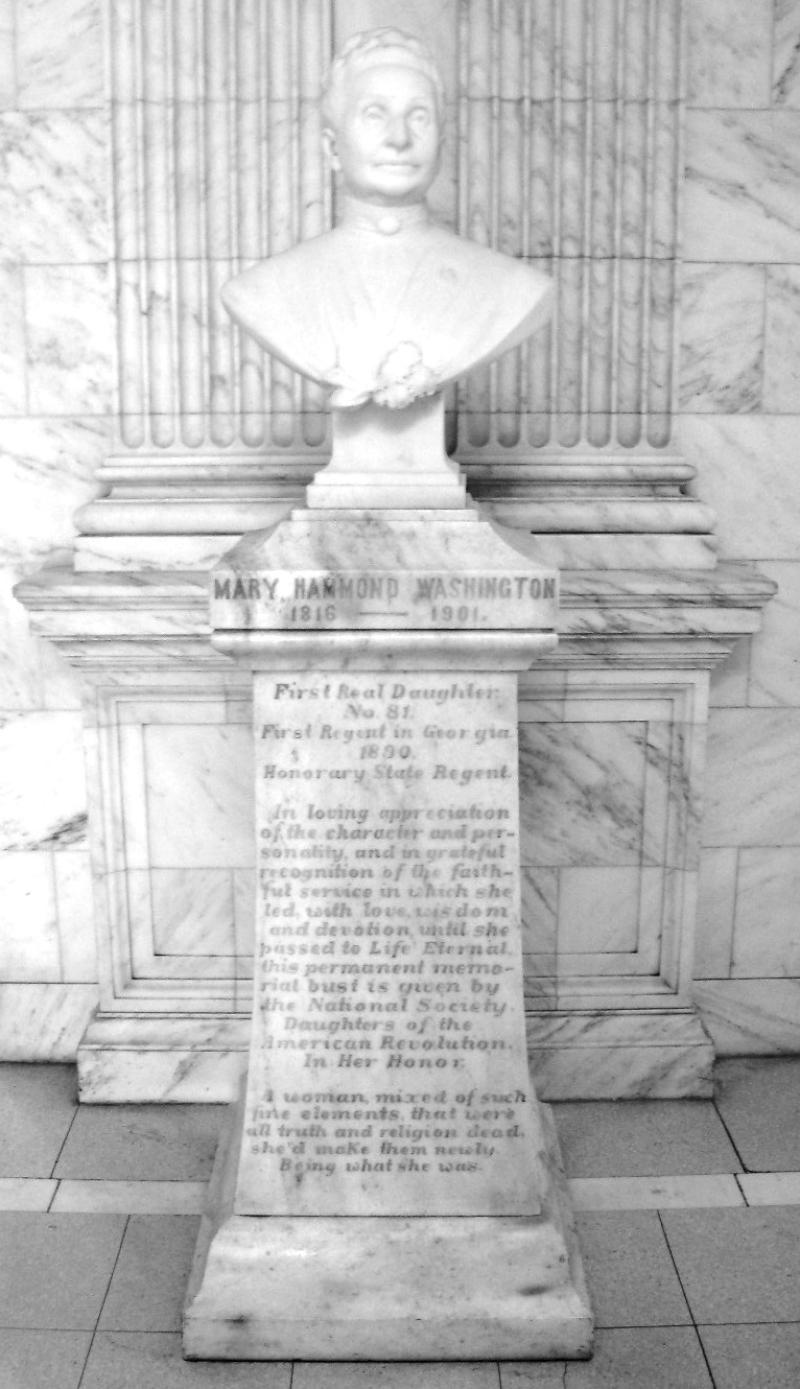

Mary Hammond Washington

National Number 81

The reason for Mary Hammond Washington’s eager participation in the Daughters of the American Revolution was, undoubtedly, the love and devotion she felt for her father and mother “whose memories” she “cherish[ed] so dearly.” Mrs. Washington was not only the first Real Daughter to join the Society but also the first member from the state of Georgia. She organized the Macon Chapter in Macon, Ga., and gathered the necessary twelve members by “making out the papers of ladies whose Revolutionary ancestry [she] knew.” Mary acted as regent of the Macon Chapter from its organization in 1893 until her death in 1901. She dutifully attended Continental Congress when she could, but when she could not attend she wrote her regrets, saying, “Please give my affectionate greeting to the Congress and let them know how much I wish to be with them.” Although she did not live to see the completion of Memorial Continental Hall, she was enthusiastically committed to its construction. At Congress in 1899, Mary was named an honorary state regent of Georgia for life.

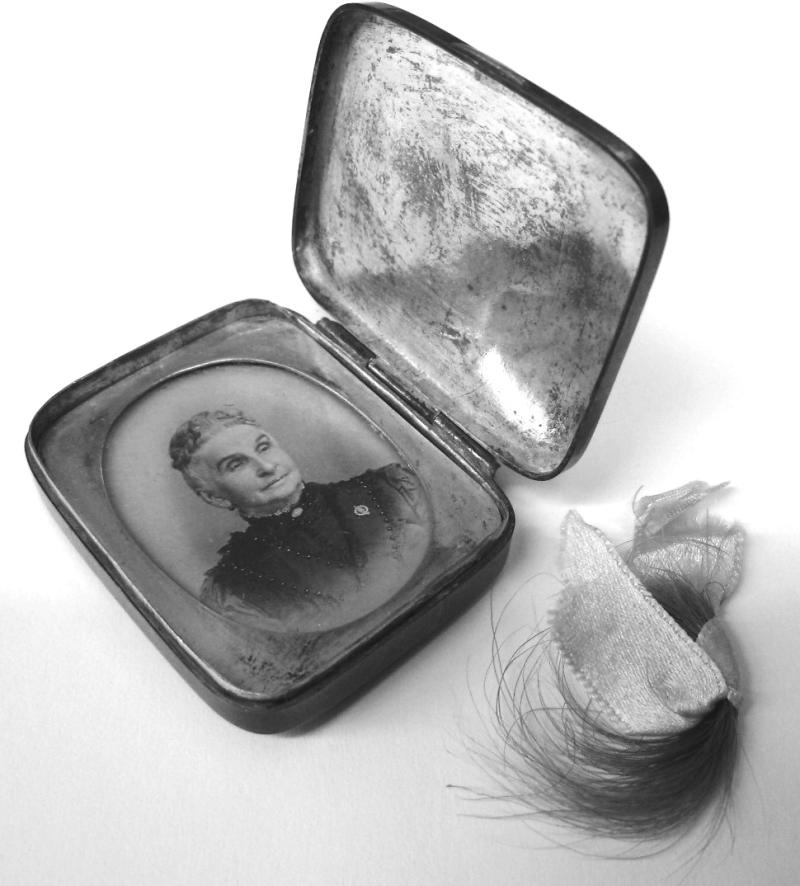

This silver locket box (pictured here), now part of the collections of the NSDAR Archives, has Mary Hammond Washington’s initials engraved on the top and a lock of her hair inside with a photograph.

Unlike many Real Daughters, Mary knew her father for many years and maintained a close relationship with him until his death. Mary was a girl of eight or nine when the Marquis de Lafayette visited Augusta, Ga., in 1825. Her father, Colonel Samuel Hammond, served on a committee to prepare a reception for Lafayette, and Mary retained a vivid memory of this event. After exceptional service in the Revolutionary War, her father settled in Georgia, where he became a member of the Georgia House of Representatives, the Georgia Senate and a Representative in the 8th United States Congress. In 1805 he was appointed Civil and Military Governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory by President Jefferson. He remained in this post until 1824 and then moved to South Carolina. He did not retire from public life until 1835, after serving as Surveyor General and Secretary of State of South Carolina.

Mary Hammond Washington

National Number 81

Mary married J.H.R. Washington, a banker and planter from Georgia, in 1835. Her daughter, Ellen Washington Bellamy, was also a charter member of the Macon Chapter. While she entertained herself with many different activities throughout her life, Mary’s later years were dedicated to the National Society. When writing to Mary Jane Seymour in 1901, Mary said, “I sincerely hope that our society will allways [sic] be a helping hand to our country.” In 1909 the Real Daughters Committee resolved to create a memorial to the Real Daughters, and Mary was chosen as the subject. A bust of her likeness was created by Italian sculptor Fidardo Landi. The bust and its pedestal were placed in Memorial Continental Hall, where they remain today as a fitting tribute to Mary and to all Real Daughters. The inscription reads in part, “In loving appreciation of the character and personality and in grateful recognition of the faithful service in which she led, with love, wisdom and devotion, until she passed to Life Eternal, this permanent memorial bust is given by the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution In Her Honor.”

Angelina Loring Avery

National Number 10301

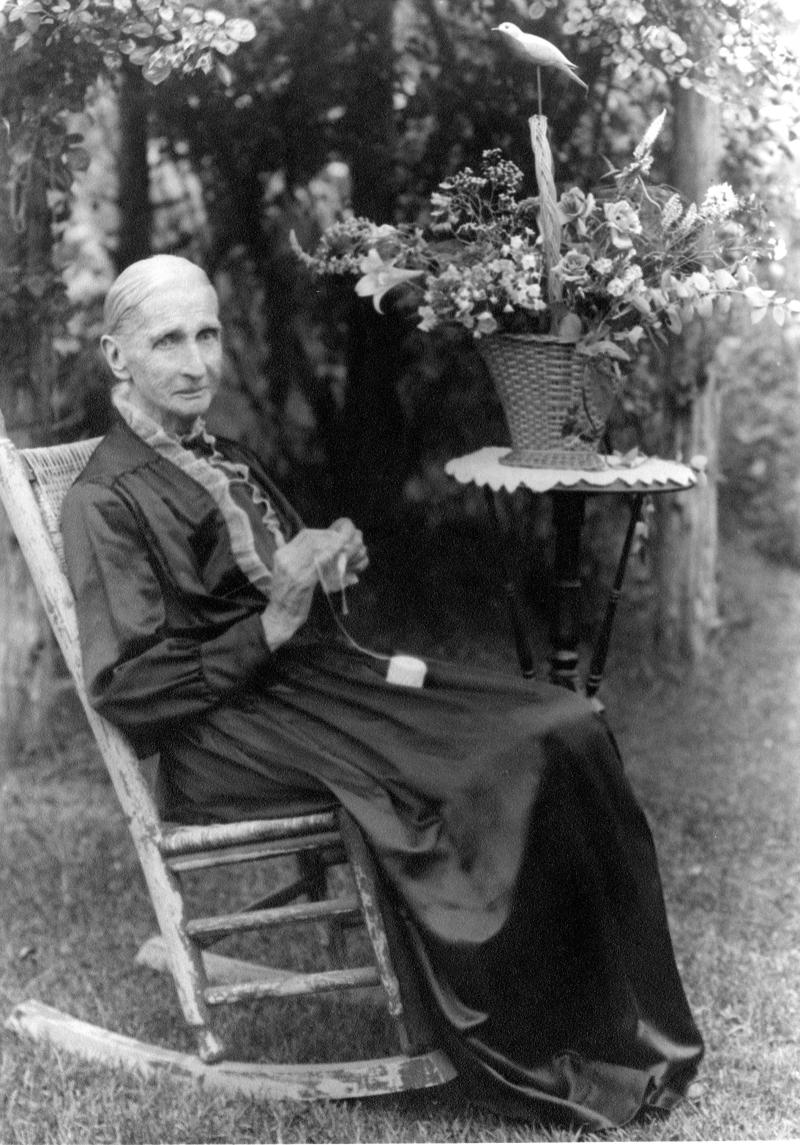

This photograph of Angelina Loring Avery was taken in 1935, just two years before she died at age 97. She was one of the last surviving Real Daughters.

Angelina Loring Avery

National Number 10301

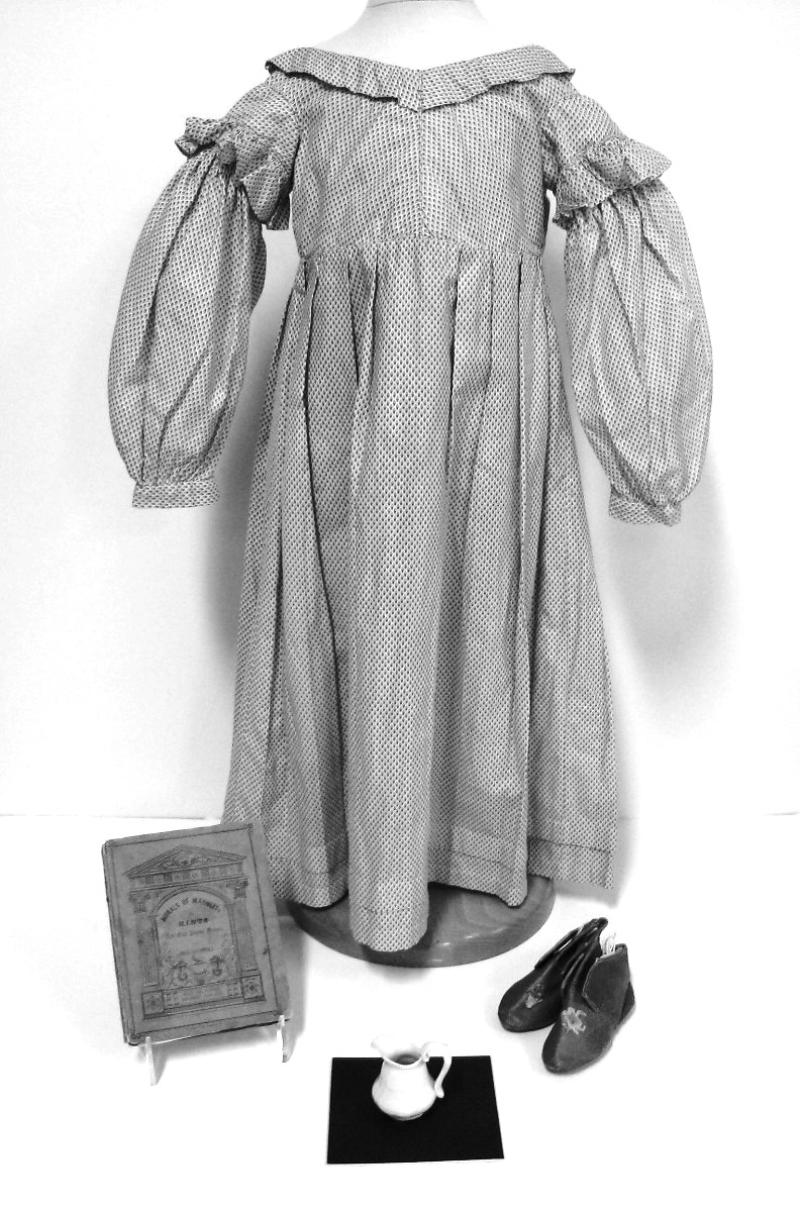

Angelina Loring Avery joined the DAR in 1895 and was a member for 42 years until her death in 1937. Angelina’s father, Solomon Loring, was in his 70s when she was born. The combined life spans of father and daughter totaled more than 171 years. Several of Angelina’s personal items, including a child’s dress, a book, a doll pitcher, photographs and baby shoes, were donated to the DAR. These items are now part of the collections of the DAR Museum and the NSDAR Archives.

Louisa Capron Thiers

National Number 10844

Louisa Capron Thiers passed away at age 111, making her the oldest Real Daughter of the American Revolution. She was born on October 2, 1814, in Whitesboro, N.Y. After her father, Seth Capron, served in the American Revolution, he studied to become a doctor under the tutelage of Dr. Basaleel Mann. Capron later opened a medical practice and married Dr. Mann’s daughter, Eunice. Louisa was one of five children from this marriage. In a letter to the DAR, Louisa reminisced about her childhood in Orange County, N.Y., saying:

I played on the bank of the Erie Canal, then being dug back of my father’s house. I rode in the first boat, called the Pumpkin Seed. I rode on the first railroad, a short line from Schenectady to Albany, N.Y., about 20 miles. I went down the Hudson river [sic] in the first steamboat at the rapid rate of about 6 miles an hour.

Louisa married David Thiers in New York City in 1847. They moved to Wisconsin in 1850, first settling on a farm, then in the city of Kenosha. In the book Sketches of Wisconsin Pioneer Women, compiled by DAR State Historian Florence Dexheimer, Louisa said they raised a family “sharing in the meanwhile with their new neighbors and friends the many privations and hardships incident to life in the middle west.”

This photograph of a young Louisa Capron Thiers appears in a scrapbook donated by her children to the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution.

Louisa Capron Thiers

National Number 10844

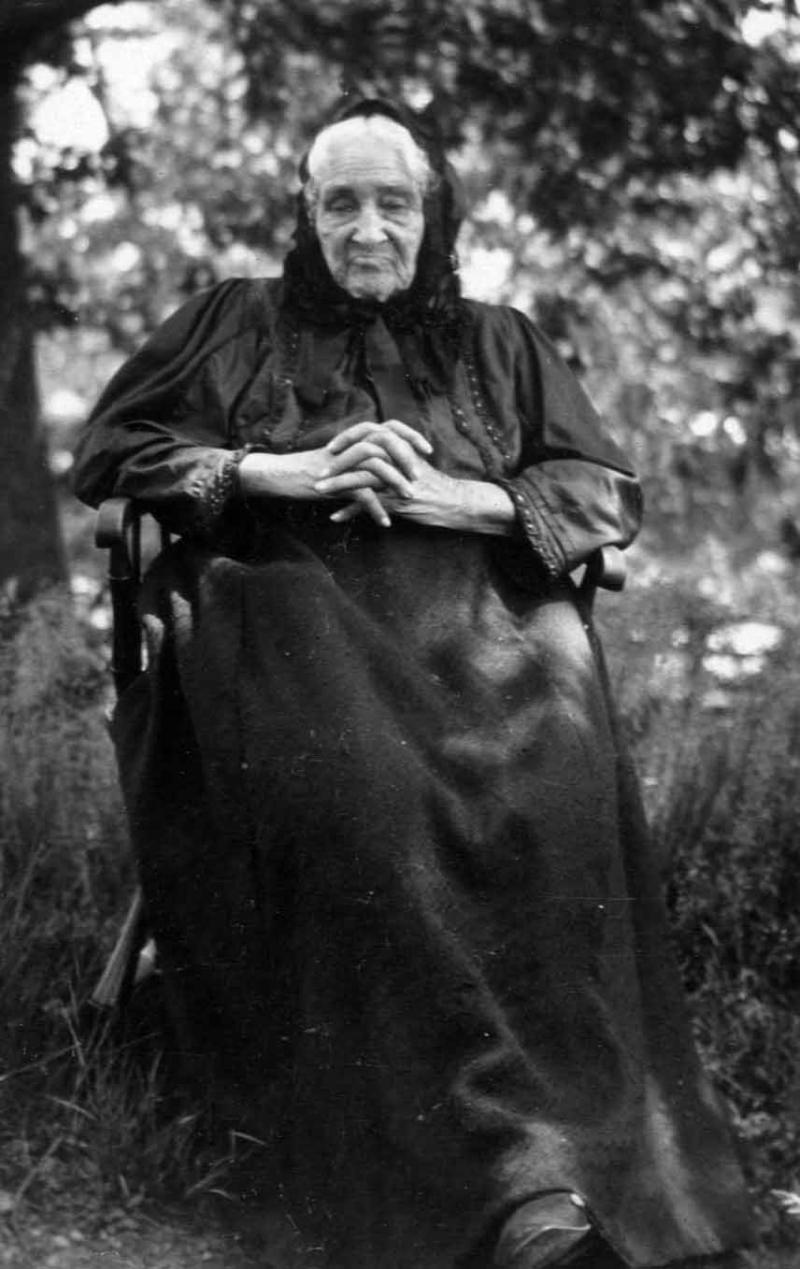

Louisa moved in with her daughter’s family in Milwaukee in 1888. She lived there the rest of her life, and the Milwaukee Chapter was proud to count her as their last surviving Real Daughter. She read, knitted, crocheted and thoroughly enjoyed her years as an old woman. When asked her secret to a long life, she said it was attributed to “a light diet, careful eating, keeping alive an interest in life and daily event, being happy myself and doing what I can to make others happy.”

Even as an elderly woman, Louisa always tried to stay apprised of current events. During World War I, she made garments for “our boys in France” and knitted socks for the French orphans. Grateful for the passing of the 19th Amendment, she proudly cast her vote for President Coolidge at age 110 and later received a thank you letter from the president. Louisa was also constantly aware of the dramatic changes that had occurred in the world during her lifetime. Writing to the DAR, she said, “Suffice to say I have seen the building of this great nation from a few States along the Atlantic coast across the continent to the Pacific Ocean.” Having lived a long life lived with such strength and character, Louisa is a model for this generation of women and for all Real Daughters.

This photograph was taken at the grave-marking ceremony for Louisa Capron Thiers in 1926. At 111 years of age, she lived longer than any other Real Daughter.

Mary Keyes

National Number 14805

Mary Keyes was a teacher in New York state when she married Reverend Nathaniel Abbot Keyes in 1839. In 1840 they traveled to Syria, where Keyes ministered for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. The couple stayed in Syria for four years, during which they lost two children and had a daughter, Harriet. They returned to New England and then moved to Princeton, Ill., in 1855, hoping the climate would improve Keyes’ health. After his death in 1857, Mary lived with her daughter, Miss Harriet L. Keyes. Both women became members of the Princeton-Illinois Chapter.

Eunice Russ Ames Davis

National Number 16263

On October 22, 1800, in Andover, Mass., Prince Ames and Eunice Russ Ames celebrated the birth of their daughter, Eunice. Prince Ames, who is listed in Forgotten Patriots as African American, was likely of African, European and American Indian descent. His wife, Eunice Russ, was biracial, having a white mother and an American Indian father. Therefore, Eunice Davis was unique among DAR’s Real Daughters because of her mixed heritage. Her passion for religion and the abolitionist movement also make her distinct.

Eunice married her first husband, Robert Amos, in 1819; they had two sons and a daughter together. The family lived in Lowell, Mass., during their marriage, but after her husband’s sudden death in 1825, Eunice moved to Boston. Her second husband, John Davis, was an African American Baptist minister. According to the Boston Daily Globe in 1897, Eunice was “of a deep religious nature” throughout her life. She became the president of the First Independent Baptist Female Society and was actively involved in her own church as well as other local black churches.

In 1833, the same year the Slavery Abolition Act passed in Britain, the American Anti-Slavery Society was founded by William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Weld and Robert Purvis. Because prominent abolitionists such as Garrison and Wendell Phillips lived and worked in Boston, the city became a center for the American anti-slavery movement. Eunice was an eager participant in this movement. She served as an officer of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society and helped to petition and gather signatures in favor of anti-slavery legislation. As Eunice aged into her late 90s, newspaper articles called her “the oldest living female abolitionist in the country.” She proudly retold stories of the exciting, but difficult, years of antebellum abolitionism.

Eunice was one of seven Real Daughters to join the Old South Chapter of the DAR. She was presented with her souvenir spoon from the National Society at her 97th birthday celebration. She died in 1901, having outlived her two husbands and three children and survived the entire 19th century.

Sophronia Fletcher, M.D.

National Number 17580

After Sophronia Fletcher, M.D., passed away on July 17, 1906, the Granite State Monthly called her “one of the first female physicians in the country and one of the oldest living members of the medical profession in the country.” She was born in Alstead, N.H., in 1806. Her father, Peter Fletcher, a Massachusetts native, joined the regiment of guards at Cambridge in July 1778 and continued his service in the war until 1780. Sophronia received an education in the schools at Milford and Hancock, N. H. Her first occupation was as a teacher in her home state as well as in New York.

Sophronia went to South Boston in 1845 and learned about the condition of mentally ill patients in asylums through an acquaintance. This prompted her interest in the study of medicine. Fortunately, she entered this field at relatively the same time as the first education programs in medicine became available for women. She enrolled in the new Boston Female Medical College (which later became part of Boston University) and was part of the school’s first graduating class in 1854. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal reported on this graduation and listed the subject of her thesis as “insanity.” Not long after becoming a medical doctor, Sophronia took a bill to the State House of Massachusetts asking that women physicians be appointed to treat both female patients in asylums and female prisoners. The bill passed successfully with the help and influence of prominent lawyer and activist, Wendell Phillips, a friend of Sophronia’s.

Combining her first career as a teacher with her new success as a physician, Sophronia became a professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Mount Holyoke College (then called Mount Holyoke Female Seminary), where she held the chair of physiology for more than 50 years. But she did not lose her progressive personality and attitude toward reform. She joined the New England Female Moral Reform Society and acted as the society’s physician for nine years. The work of the society, which was reported in the annual report of the Board of State Charities of Massachusetts, included the “reformation of fallen women” and providing “temporary shelter and employment” to “poor and friendless females.”

Sophronia joined the Old South Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1897. In her later years she lived with her niece, Dr. Leonora Lathe, in Cambridge, Mass. She remained interested in reform movements and philanthropy until her death at almost 100 years old.

Julia Stone Towne

National Number 20903

Almost 100 years after the death of Real Daughter Julia Stone Towne, her great-great-granddaughter discovered a continuous series of correspondence between Julia and her daughter, Mary Julia Towne, which revealed a rare insight into the lives of American women in the mid-19th century. Katherine Morgan published these letters of her ancestors in a book titled My Ever Dear Daughter, My Own Dear Mother. In her introduction, Morgan discusses the difficulty in tracing the female side of her family tree, while men could be traced through “deeds, wills, probate inventories, military discharges and even their memoirs.” Morgan goes on to say:

Without these letters, these two women would be nothing more than names on the family tree. The letters, however, make it possible to recreate their lives and demonstrate the importance of women’s lives in spite of the neglect by genealogists and historians.

While Julia and her daughter lived relatively ordinary lives, they are extremely significant because they represent scores of other women from the same period whose letters were not saved and whose emotions and experiences were not recorded for posterity. Their correspondence unveils the challenges and struggles many women must have faced, along with their successes and deepest hopes.

Julia Stone Towne

National Number 20903

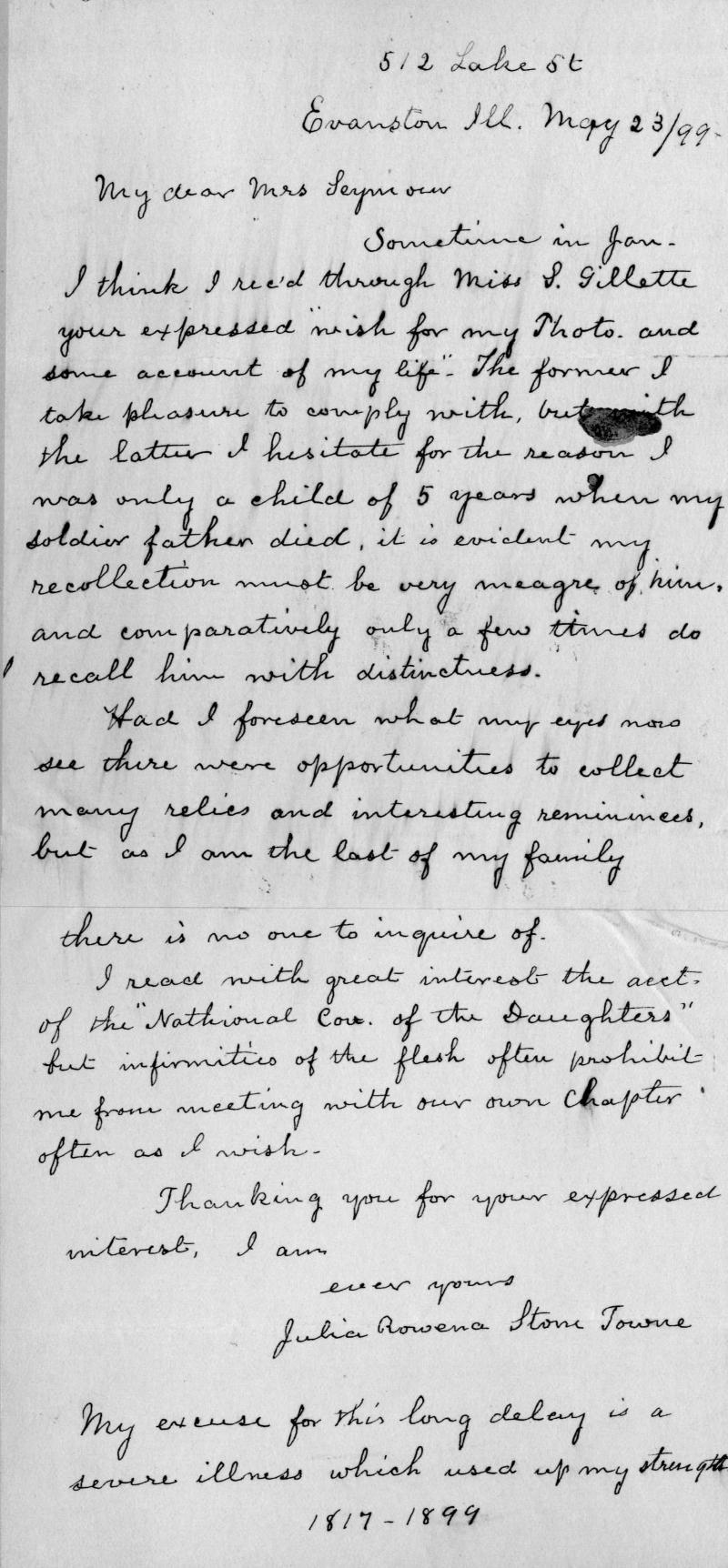

Julia was born the youngest of 13 children in Marlborough, N.H., on September 26, 1817. Her father died in 1823 when Julia was only 5 years old. In a letter she wrote to DAR in her later years, she says “it is evident my recollection must be very meagre [sic] of him and comparatively only a few times do I recall him with distinctness.” She lived with her mother until the late 1820s or early 1830s, when she enrolled in Topsfield Academy in Topsfield, Mass., where her brother had opened a medical practice. In Topsfield she met Ezra Towne; they were married in 1837. The Townes lived the next 30 years in and around New York City. They had four children: William, Charles, Mary and Edward.

In 1866, the Townes moved back to Topsfield and into Ezra Towne’s family home, where several relatives were already living. The correspondence between mother and daughter began when Mary moved to Chicago to seek employment. Being so far away from her home and her mother, Mary wrote of homesickness when she first came to the city. But she soon earned a license in teaching and gained a strong sense of confidence and accomplishment in making her own money. Julia’s letters attempt to comfort and encourage her only daughter during her initial concerns and then to celebrate her newfound courage. Julia also shares with Mary her own struggles to “fit in” in the society of Topsfield. She describes a life of domesticity that revolves around housework and the family.

In this letter to the DAR, Julia Stone Towne writes about her father and her family, saying, “Had I foreseen what my eyes now see there were opportunities to collect many relics and interesting remininces [sic] but as I am the last of my family there is no one left to inquire of.”

As the stories unfold in their letters, Julia and Mary unknowingly “offer a glimpse into the multiple worlds of women in the 19th century.” Mary, a single woman living in the city of Chicago, tends to write about major events in the country and the world, her work as a teacher, her roommates, travel experiences and finally her decision to marry and give up her independence. In contrast, Julia’s letters tell of small-town life, frustrations with the local society, her basic domestic routines, widowhood and her decision to move to the Nebraska frontier to live with her son. Through this correspondence, the modern reader is given an example of a woman’s life from young adulthood to old age, as well as a better understanding of the changing roles and attitudes of women.

Julia joined the Fort Dearborn Chapter in Evanston, Ill., in 1897. She was living with her daughter, who was also a member of the Fort Dearborn Chapter, in the last years of her life. She died in 1905 at age 87. Fortunately, a large portion of Julia’s life will be preserved in her own words and will continue to represent “all of those who are nameless in the annals of history.”

Julia A. Demary and Elizabeth Russell

National Numbers 81628 and 81634

Julia A. Demary and her twin sister, Elizabeth Russell, were born when their father, John Frank, was 81 years old. Julia and Elizabeth are the only set of twins among the Real Daughters. So great was their father’s delight when they were born that he is said to have rushed out into the street to call the neighbors to come in and see his daughters. He lived to be 95 years old, and died of sunstroke after attempting to shingle the roof of his house on a hot day.