October 2, 2013 - August 30, 2014

It's human nature to like shortcuts; people are always seeking ways to save time or take the easy way out. An office supply store even markets a bright red "Easy" button for its products. The quest for comfort and efficiency in the home evolved through discovery and innovation, which led the way for dramatically improved living standards.

This exhibition illustrates how almost 150 years of inventions have basically made our lives easier, and our homes more comfy and convenient. It demonstrates that the way we work and play today has benefited from scientific experimentation and discovery from colonial times onward.

While much of modern life today powers up by the mere flick of a switch or press of a button, countless devices we now take for granted can trace their origins to more humble hand-powered beginnings. And the motivation behind plenty of this ingenuity and inspiration can be directly connected to saving time and saving energy.

We invite you to click on the topics and take a technological ride through the ages.

Cleaning

Washing Clothes

Women faced the backbreaking task of washing clothes; there was nothing easy about it. Everything associated with this burden, including filling the wash tub, was accomplished by hand. With no automatic agitation, liquid detergents or spot cleaners available, a great deal of exertion went into scrubbing, wringing and literally beating the dirt and grime out of garments, after which they had to be rinsed in a separate tub and hung up to dry.

In an effort to ease the laundering hardship, hundreds of patents were issued for all sorts of washing machines. Still these machines continued to be manually powered by foot or hand. The advent of electrically powered agitators and wringers on washing machines in the early 20th century began to change wash day for the better.

Cleaning

Washboard, 1898-1906

Earthenware and poplar

Western Reserve Pottery Company

Warren, Ohio

Washboards, made of various materials, helped ease the clothes-cleaning chore. Garments, soaked in hot soapy water and wrung were then rubbed against a washboard's ridged surface to force soap through the cloth to carry away dirt, after which they were rinsed.

1.1

Cleaning

Wash Tub, modern

White oak and iron

It took at least two heavy tubs like this to complete the washing cycle from scrubbing, rinsing and whitening or what used to be called "blueing." when adding a trace of blue color to slightly off-white fabrics makes them appear whiter. Strange, but true.

Cleaning

Washing Machine, 1910-1920

Cedar, cast iron and steel

Knoll Manufacturing Company

Reading, Pennsylvania

The early washing machine here is essentially a washtub with an agitator attached to a hand crank. Although this tub may have eased exertion in the scrubbing process, the housewife still had to fill it, turn the agitator, empty the tub, and wring and rinse the clothes.

1.2

Cleaning

Ironing

Housewives dreaded ironing especially in the summer months because no matter the melting temperature outside, a fireplace or stove inside had to be fired up to constantly reheat the heavy flatiron. For efficiency's sake, households often possessed two flatirons so that one could be heating while the other was in use. By the late 19th century, gas-powered irons saved the housewife from heating and reheating flatirons on the stove. While this new source of heat shortened the ironing time, the gas iron still radiated a high temperature. Charles E. Carpenter changed ironing day forever when he introduced the first practical electric iron in 1890. Just plug it in and it was pretty much ready to go.

Cleaning

Flatiron, 1795-1825

Cast and wrought iron

United States

Early irons comprised two types: box charcoal irons with a special compartment in which to place hot coals; and the flatiron, featuring a thick slab of cast iron like this one, which had to be constantly reheated on the stove or in the fire.

1.10

Cleaning

Gas Flatiron, 1900-1925

Cast iron, nickel plating, wood, brass and cloth

J.B. Colt Manufacturing Company

Chicago, Illinois

Although the gas-powered iron shown here eliminated the need for trips to the stove, fuel-heated irons were a fire-risk and produced a great deal of heat from the burner inside.

1.11

Cleaning

Electric Iron, 1907-1917

Cast iron, steel, copper wire, brass and wood

General Electric Company

Schenectady, New York

Electricity improved ironing efficiency with the heat regulated in the bottom. The wood handle was cool to the touch.

1.12

Cleaning

House

Like washing day, house cleaning was a laborious task often reserved for springtime. Spring cleaning meant sweeping, scrubbing and whitewashing every room from top to bottom. Inventors of the 19th century sought new ways to make the housewife's cleaning rigor easier and more convenient. The carpet sweeper, first patented in 1858, worked much like those of today with a revolving brush that picked up dirt into a collection pan. The concept of creating a vacuum to suck up dirt from surfaces came about in the 1860s. Vacuums using bellows to create suction still required hand operation. Electricity offered the housewife more convenient housekeeping. First patented in 1901, the earliest electric vacuum cleaners were large and delivered to the house by truck. Smaller motors allowed for lighter portable models by the 1910s.

Cleaning

Broom, 1790-1825

Birch

United States, possibly Massachusetts

Sometimes low-tech is the best tech. In this case, the simple broom represented one of the housewife's most important cleaning implements. While not playing a central role in today's households, just about every home continues to possess this essential sweeping tool.

1.7

Cleaning

Carpet Sweeper, 1885-1900

Painted wood, animal hair bristles, steel and rubber

Bissell Carpet Sweeper Company

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Though not the first, Melville R. Bissell received a patent for a perfected mechanical carpet sweeper in 1881. Pushing the sweeper rotated a brush that picked up dirt and deposited it into trays inside, making sweeping faster and more convenient. Sweepers were quiet, lightweight and usually fitted with a long handles so they could be pushed without bending over.

Cleaning

Bellows Vacuum, 1910-1915

Oak, pine, cast iron, nickel-plated steel, brass and leather

England

Instead of sweeping away dirt, this vacuum cleaner sucked it up using hand-operated bellows. Unfortunately, it took two people to run this model: one to pump the bellows while the other used hose and brush attachments to suck up the dust that was collected in a cotton bag within the machine, not exactly convenient or efficient

1.8

Cleaning

Electric Vacuum, 1910-1920

Oak, steel, aluminum and fabric

The Regina Company

Rahway, New Jersey

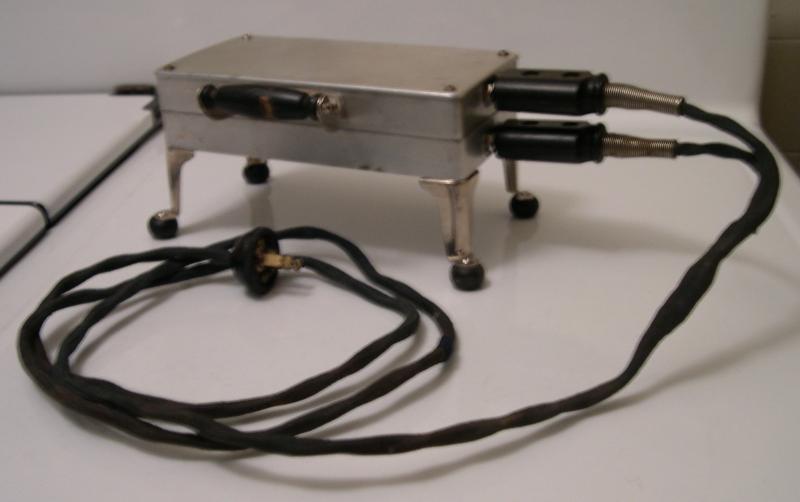

The strange-looking object here is actually an electric vacuum cleaner. The Regina vacuum cleaning company made both bellows and electric models. Regina, which focused on improving the style of vacuums, as well as easing the way they handled, advertised them as light, neat, compact and easy to use. There's that word "easy" being used to describe a new product!

Cleaning

Sturtevant Vacuum Cleaner, 1913

The House Beautiful

Western Electric

The weight of vacuums must have concerned consumers in the early days because advertisements from that time made special mention of this issue. This one boasts that even a child could use and carry a vacuum. Note that the ad most focuses on equating ownership of this "ultra convenient" vacuum cleaner with being a modern and enlightened woman in a home "where the drudgery and inefficiency of the broom are no longer known."

Cleaning

Personal Hygiene

Today, we step into our bathroom daily to bathe or shower and emerge fresh as a daisy. This wasn't always the case; keeping clean was a tiresome chore in the old days. Taking a bath meant heating water, a lot of it, in the fireplace or on the stove and pouring it into a tub (that had to be dragged out from storage somewhere and usually placed in the kitchen), a nuisance in which most people rarely participated. Instead, everyone opted to use a washbowl and pitcher for freshening up.

When nature called, the refuge of a bathroom with automatic toilet was nowhere to be found. Everyone used either the privy (aka outhouse) or a chamber pot, which required daily cleaning. Bathrooms made personal hygiene more convenient for both users and the housewife. Modern-looking bathrooms, equipped with a sink, toilet and tub originated by the 1850s. Plumbed bathrooms became standard in middle class urban homes by the 1920s. With the turn of a faucet, hot and cold water were dispensed at a moment's notice.

Cleaning

Wash Stand, 1835-1845

Painted Poplar

United States, possibly New York

No bathrooms, no bathroom sinks or tubs or showers or faucets are pictured here. When someone wanted to wash up, he or she filled the pitcher daily, poured water into the bowl and scrubbed from there.

1.3

Cleaning

Wash Bowl and Pitcher, 1835-1853

Transfer printed earthenware

C. & W.K. Harvey

Longton, England

1.4

Cleaning

Chamber Pot, Modern

Tin-Glazed Earthenware

Chamber pots provided a convenient alternative to using the outhouse. Usually placed in the bed room, chamber pots could also be found in other areas of the house like the dining room. Daily emptying of these aromatic receptacles fell to the housewife or servant. To cut down on the smell, some were equipped with covers.

1.37

Cleaning

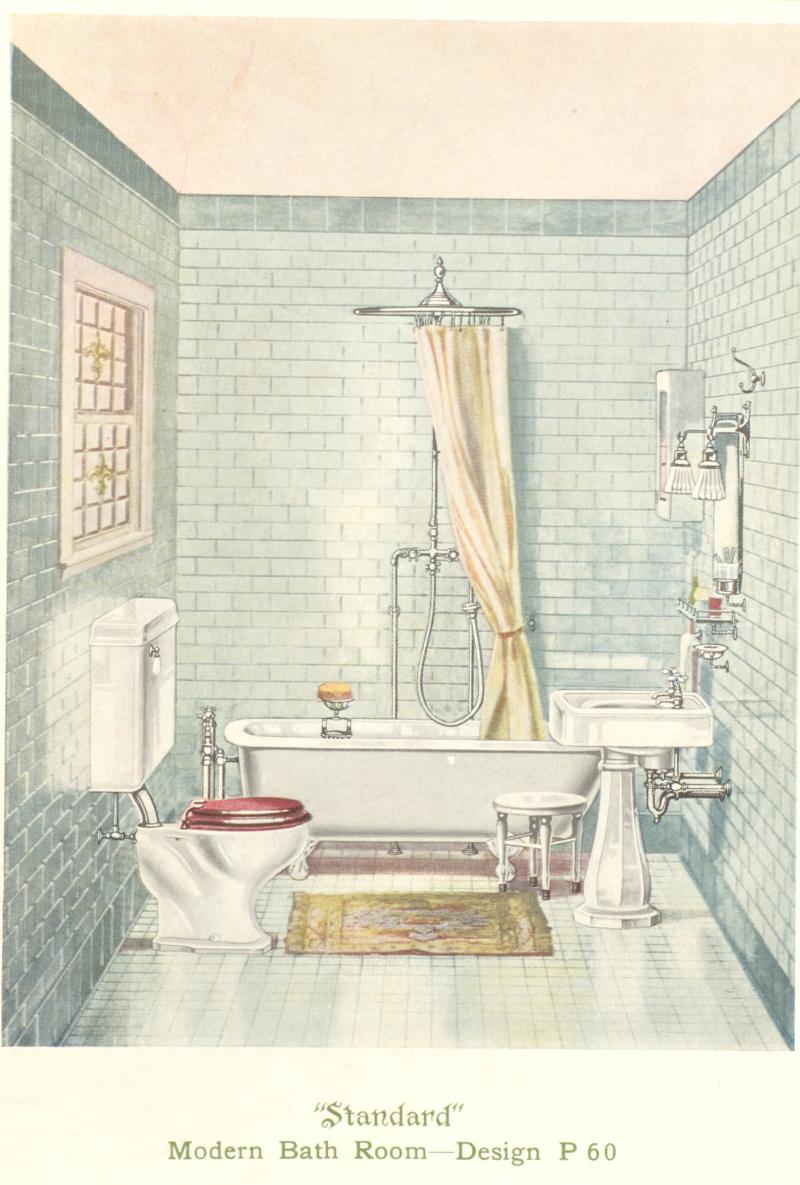

Modern Bath Room, 1911

Catalog "P"

Since habits are difficult to break, some homeowners installed plumbed sinks in the bedroom in place of the wash stand because that was the traditional location for this personal chore. At some point, however, someone figured out it made more sense to situate all of plumbing in one line in one place so a separate room was created to contain it all. The bathroom was born.

This design here more closely resembles today's bathrooms. Gleaming tile throughout, smooth white porcelain and shiny nickel-plated hardware became the standard for the modern bathroom by the 1910s. Exposed plumbing and antiseptic surfaces were considered easy to keep clean .

1.27

Lighting

Candlelight

Artificial lighting in the home was regarded as a luxury. During the day, people used natural light to illuminate their work, reading, cooking, sewing and other everyday needs. At nighttime, candles were used sparingly because of their expense and their need to be carefully tended to avoid igniting a house fire. Cheaper rush candles were also used. Women and children gathered rush, a plant material, in late summer while still green. Rush stalks were peeled, dipped in tallow (or other household fat) and placed outside to dry after which they were ready to use.

Lighting

Candlestick, 1790-1810

Brass

England

2.1

Lighting

Candle Mold, 1780-1820

Tin

Possibly the United States

Tin molds, such as the one here, were used to make better quality candles. A knotted wick was passed through a bottom hole and melted tallow was then poured in to fill the tube.

2.2

Lighting

Rush Lamp, 18th Century

Wrought iron and wood

United States

In this dual-purpose lamp, when used as a rushlight, fat-coated rush was placed between pincers and burned like a candle. A candle was placed in the other side when using the lamp as a candlestick.

2.4

Lighting

Oil

To produce a bright light in the home, housewives also used oil lamps, the simplest of which resembled their ancient predecessors. Depending upon the type of oil used, an oil lamp smelled worse than tallow and gave off a black plume of smoke. Oil could be extracted from fish, animals, and later in the 19th century, vegetables and minerals.

Beginning in the 18th century, inventors and scientists worked on ways to improve lighting. Experiments focused on increasing efficiency and producing a brighter burning flame. In 1783, Frenchman Ami Argand patented a new type of oil burning lamp comprising a cylindrical wick held between metal tubes. The cylindrical assembly created a draft like that of a chimney allowing the flame to burn brighter. After its discovery in Pennsylvania in the late 1850s, kerosene became the fuel of choice because of its cheap price tag, replacing whale and colza oils by the 1860s.

Lighting

Oil Lamp, 1700-1710

Wrought iron and brass

Pennsylvania

Oil lamps like this one date back to ancient times. Oil was poured inside the vessel and a wick, either cloth or rush, placed in the spout and lit. It burned like a candle. The hook allowed the user to suspend it from the ceiling.

2.3

Lighting

Argand Lamp, 1820-1830

Copper-plated silver

England

In addition to improved brightness, an Argand lamp required less frequent wick trimming because of its more complete combustion of the wick and oil. As a result, Argand lamps quickly caught on and famous Americans like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson bought them for their homes. Gravity fed oil from the reservoir located in the urn through the horizontal arm to the cylindrical wick.

2.5

Lighting

Sinumbra Lamp, 1830-1840

Brass, iron and glass

Cornelius & Co.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A new type of Argand fixture, called the sinumbra lamp, was patented in England in 1820. Sinumbra, meaning "without shade or shadow," cast no offending shadow upon the surface under illumination. The shadowless principle was accomplished by placing the fuel reservoir in a ring above the burner.

2.7

Lighting

Solar Lamp, 1849-1855

Brass, iron, marble and glass

Cornelius & Co.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Improvements in air circulation between the burner and wick allowed the flame to burn brighter than the sinumbra lamp. People referred to these devices as "solar lamps" because the illumination was thought to be "comparable to sunlight".

2.6

Lighting

Oil Lamp, 1830-1840

Blown and molded glass with metal alloys and tin

Boston and Sandwich Glass Company

Sandwich, Massachusetts

The wick in this lamp was suspended in fuel, either whale or colza oil.

2.9

Lighting

Kerosene Lamp, 1880-1890

Molded glass, brass, iron and steel

United States

Tall kerosene lamps like this one were placed on a center table and helped light an entire room.

2.10

Lighting

Gas

Impurities in manufactured gas made it foul-smelling and dirty. Nevertheless, an early user exclaimed "this day I lit for the first time the Gas, and a very splendid light it makes." Gas was usually made from burning coal. However, it could also be distilled from other flammable sources like benzene and resin.

Gas made light convenient by merely turning on a valve, which meant no more cleaning of all those oil lamps and candle holders.

Since fixtures had to be tethered to supply pipes, they weren't portable, which led to centrally locating chandeliers in ceilings. Rubber hoses connected table lamps to a chandelier for task lighting.

The light produced by gas wasn't much brighter than that from an Argand lamp and inventors sought to improve its illumination. In 1885, Viennese chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach developed a brighter gas lamp. It consisted of a fabric mesh mantle coated with a non-burning mineral which when heated by the gas flame glowed white-hot. This glow, or incandescence, produced a brilliant blue-white light that did not flicker or snuff out at a slight draft. Welsbach invented his mantle, in part, to compete with the new electric bulb.

Lighting

Gas Lamp, 1840-1850

Cast brass, iron and cut glass

Messenger and Co.

England

This lamp was powered by gas and permanently fixed in place.

Lighting

Gas Meter, 1870

Painted and tin-plated sheet iron, brass, glass and paper

P. Hodge

Seneca Falls, New York

Gas lamps = utility company = gas meter = gas bills! The early 1830s brought the introduction of the earliest gas meters to homes in the United States. Similar to this patent model, they would have been placed in a utilitarian area like the cellar. Once that meter was installed, a gas man noted meter usage and the gas company sent the bill to the homeowner based on that calculation.

2.12

Lighting

Table Lamp with Gas Supply Hose, 1855-1865

Zinc, brass, wood, cloth and glass

Cornelius & Baker

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Gas was supplied to this lamp by the rubber supply hose that connected to a burner in a chandelier.

2.13

Lighting

Welsbach Gas Mantle with Box, 1875-1900

Brass, cotton, glass and wood

Welsbach Incandescent Gas Light Company

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The Welsbach mantle actually glowed brighter than even early electric bulbs because of the incandescence of the oxides infused in the gauze. Today, mantles, which are ceramic mesh that case the flame produced by the lantern, are most often used in portable camping lanterns.

2.15

Lighting

Electric

Scientists of the 18th century studied the principles of electricity, but not the practical side because nobody had yet figured out how to apply it to everyday life. The light bulb, invented in 1879, would not have moved beyond the laboratory had it not been for Thomas Edison. Edison conceived the idea of bringing electricity to houses and businesses through wires connected to power generating stations, which made electric lighting practical for home use. Edison opened the first power station in the United States on Pearl Street in New York City in 1882.

Lighting

Light Bulb and Socket, Early 20th Century

Glass, brass, tungsten filament, ceramic, copper wire, rubber, cotton, steel and pine

United States

2.16

Lighting

Light bulbs, 1910s

Glass, brass, tungsten filament, ceramic, copper wire, rubber, cotton, steel and pine

United States

Like today, light bulbs came in a variety of shapes and colors.

2.35

Lighting

Table Lamp, 1905-1913

Bronze, iron, copper and glass

Duffner & Kimberly

New York, New York

Unlike gas power, the fueling of which limited design choices, electricity freed lighting designers to create an infinite array decorative fixtures. This lamp could be placed in a room anywhere near a socket receptacle.

2.17

Cooking

Open Hearth

No microwaves here! A housewife living in 18th or early 19th century cooked in a large open hearth fireplace, which allowed the creation of multiple mounds of glowing coals for more controlled food preparation than could be offered by a single blazing fire. The fireplace was equipped with simple iron cranes, upon which pots could be suspended and their heating manipulated by the experienced cook who knew just how long and how far to keep them from the heat source to produce a perfect meal.

Cooking

Roaster, 19th Century

Tin-plated sheet iron

United States

For centuries, raw meat was skewered onto a rotisserie spit inside a roaster and turned by hand. Rotation cooks meat evenly in its own juices and allows easy access for continuous self-basting. The door in the front of a rotisserie allowed the cook to monitor the roasting process.

3.8

Cooking

Waffle Iron, 1785-1810

Cast and wrought iron

United States

The user slid this waffle iron, filled with yummy batter, into hot coals for cooking. The handle was purposively fashioned long so it could be used to safely pull out the baked cake away from the heat and flame.

3.9

Cooking

Toaster, 18th Century

Wrought iron

Possibly Pennsylvania

In the odd-looking contraption pictured here, the user toasted bread with one side facing the fire. Nimble fingers were required to quickly flip the bread around for toasting the other side.

3.5

Cooking

Heat Regulation

By the late 18th century, technology entered the kitchen when inventors and scientists developed new methods of heat regulation making cooking more efficient. The housewife of the mid-19th century cooked on an entirely enclosed cast-iron range powered by coal or wood, which allowed her to conveniently place pots and pans directly on burners. Though cooking with an enclosed range offered [somewhat] controlled heat, time was still required to chop, store and replenish kindling to keep the fire tended.

Cooking

Oven Door, 1800-1825

Cast iron

United States

This heavy iron door kept heat inside the oven where it could do the most good!

3.1

Cooking

Gas and Electric

Looking for other uses for their product, gas companies began offering cook stoves by the 1860s. An early advertisement noted that "the gas-consuming stove…has neither smoke nor dust, and saves both time and fuel." The discovery of natural gas reserves in the South in the early 20th century made cleaner-burning natural gas a viable fuel alternative.

Inventors saw potential in using electricity for more than just lighting. Starting in the early 1890s, electrically powered cooking appliances made their debut. Cooking with electricity developed slowly because of the high cost and unreliability of early appliances. Nevertheless, George A. Hughes developed the first stove around 1904, followed shortly thereafter by General Electric Company with its model in 1907. Subsequent improvements, including the oven thermostat and better heating elements, made it more practical and convenient for the housewife. Manufacturers claimed that owning an electric stove spared the housewife from spending too much time in the kitchen. There's that "time saving" phrase again.

Cooking

Water Kettle, 1875-1925

Brass, copper and cast iron

England

Small heating appliances were adapted for gas power allowing, for instance, water to be conveniently heated in the parlor at tea time instead of away from guests at the kitchen stove.

3.2

Cooking

Table stove, 1855-1860

Cast iron and brass

United States

A variety of appliances including a chafing dish, water kettle or coffee pot could have been used on this gas-powered table stove.

3.3

Cooking

Electric Stove, 1910-1912

Painted sheet steel and cast iron with nickel-plated brass, porcelain, glass, cloth and rubber-covered copper wire

Simplex Electric Heating Company

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Though this stove resembles the gas- or coal-powered variety, it was electrically powered. The knobs on the front, with low, medium and high settings, regulated the elevated burners, griddle and oven below.

3.24

Cooking

Electric Kitchen, 1899

Simplex Electric Heating Company

Cambridge, Massachusetts

The chef seen in this image proudly admires his modern electric kitchen. The "stove" comprises a wooden table fitted with receptacles, which received plugs from the water kettle, coffee pot, chafing dish and skillet placed on the table top. This setup was familiarly called the "wood range."

3.34

Cooking

Electric Cooking Appliances

Starting around 1890, inventors developed all sorts of electric cooking accessories including frying pans, water kettles and chafing dishes. At first, housewives didn't fully accept electric cooking appliances because the heating elements burned out quickly. Initially, power companies offered service only in the evening making electricity expensive and inconvenient. Once service was extended, electricity costs dropped, which, in turn, encouraged more households to purchase these novel electric devices.

Reliability and daily service also persuaded housewives to use electric cooking appliances at the dining table where their portability allowed them to easily plug into a nearby light socket. This made them more convenient than fuel- burning models because the heat came at the flip of a switch.

Cooking

Frying Pan, 1907-1915

Aluminum, steel, porcelain, ebonized wood

General Electric Company

Schenectady, New York

A totally up-to-date housewife used small appliances, like this frying pan, at the dining table.

3.15

Cooking

Coffee Percolator, 1910

Nickel- and tin-plated copper and brass, glass, porcelain and ebonized wood

General Electric Company

Schenectady, New York

This percolator worked on the French drip method. The user placed a layer of coffee grinds on the screen in the glass globe and filled the urn with water. As the water boiled, a vacuum forced it up a central tube into the globe. The water percolated through the coffee grinds and collected back in the urn.

3.16

Cooking

Kettle, 1907-1915

Nickel- and tin-plated copper and brass, porcelain, ebonized wood, rubber, silk- and rubber-coated copper wire

General Electric Company

Schenectady, New York

To quote the popular TV chef, Emeril Lagasse, "BAM!"—now water could be heated conveniently with the flip of a switch at the table.

3.17

Cooking

Toaster, 1908-1909

Tin-plated steel, nichrome wire, porcelain, rubber, silk- and rubber-coated copper wire

General Electric Company

Schenectady, New York

Preparation of hot, crispy and golden-brown toast could be accomplished at the breakfast table. The user had to mind this device carefully, however, because the wire frame grew very hot and could burn the bread quickly. Only one side of the bread could be toasted at a time.

3.22

Cooking

Cord, 1910s

Silk- and rubber-coated copper wire, porcelain and steel

General Electric Company

Schenectady, New York

Since light sockets doubled as plug receptacles, appliance cords came equipped with this special screw-in attachment to twist into them.

3.38

Cooking

Coffee Pot, 1891-1896

Nickel-plated spun and cast copper and brass, cast iron, porcelain, copper wire and walnut

Carpenter Electric Heating Manufacturing Co.

Saint Paul, Minnesota

Midwest manufacturer Charles E. Carpenter began making a variety of electric appliances around 1890. This coffee pot was one of his earliest products.

3.14

Cooking

Chafing Dish, 1905-1913

Nickel-plated brass, steel, porcelain, glass and ebonized wood

Simplex Electric Heating Company

Cambridge, Massachusetts

How convenient is that? The lady of the house often treated visiting friends to a quick meal heated in the chafing dish right in the parlor or dining room.

3.18

Cooking

Waffle Iron, 1918-1920

Aluminum, nickel-plated steel and brass, ebonized wood, Bakelite, cloth and rubber-coated copper wire

Landers, Frary & Clark

New Britain, Connecticut

Pass the maple syrup please! Instead of withering over a hot stove, the housewife could coolly prepare waffles at the breakfast table for her waiting, hungry family.

3.19

Cooking

Standing Mixer, Late 1920s

Aluminum, nickel-plated brass, steel, cast iron, Bakelite, rubber-coated copper wire and porcelain enamel

Landers, Frary & Clark

New Britain, Connecticut

Electric mixers, especially lightweight models with fast motors, revolutionized kitchens in the 1910s and 1920s. Early models were equipped with no speed variation at all, just on or off. Later versions came with different speeds or types of mixing options such as beat, whip etc.

3.21

Cooking

Pyrex

Corning Glass Works introduced clear glass bakeware called Pyrex in 1908. Pyrex is borosilicate glass made from silica and boron oxide, a formula that makes it resistant to breaking from extreme temperatures. Founded in 1851, Corning Glass established one of the first industrial research labs in 1908 and had a history of science-based innovations following World War II. It is still in business today as Corning Incorporated.

Cooking

Pyrex Casserole, 1915-1925

Borosilicate glass

Corning Glass Works

Corning, New York

The first product sold was a pie plate quickly followed by many other shapes spurred on by its popularity among housewives who discovered that food seemed to cook more evenly in it. Today, almost 100 years later, many households contain a Pyrex product, often the ever-popular measuring cup with the bright red lines and numbers.

3.12

Cooking

Tea Pot, 1922-1934

Borosilicate glass

Corning Glass Works

Corning, New York

The housewife could pour hot water directly into this pot and brew tea before her very eyes. Unfortunately, she could not put the tea pot directly on the stove, a problem solved by the introduction of Flameware in 1935, which could be placed atop a burner.

3.13

Cooking

Look right through. 1916

Corning Glass Works

Corning, New York

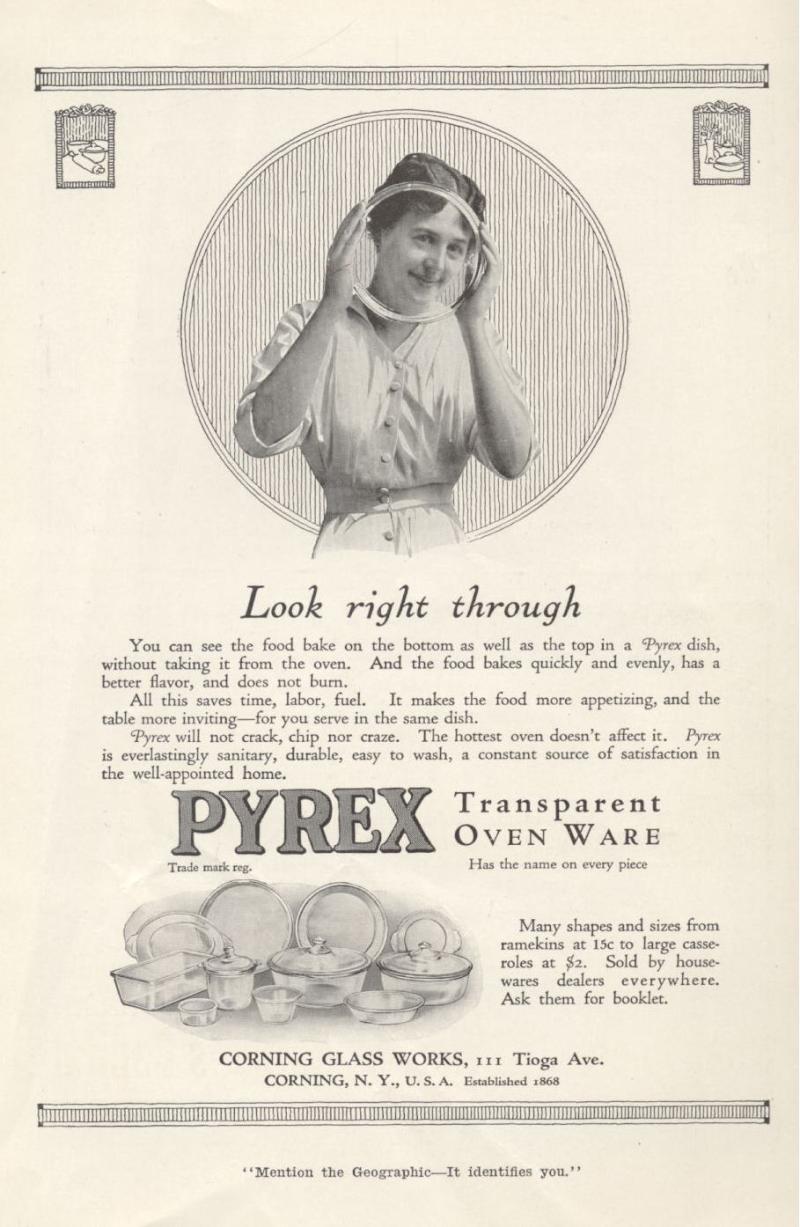

National Geographic Magazine

The Corning Glass Works promoted Pyrex as better than cooking in "old- fashioned" metal. As can be read, the ad covers just about every feature one would want in a cooking dish from making food taste better and bake more evenly to being everlastingly sanitary, durable and easy to wash. Note the word "easy" in the promotional material.

3.33

Heating and Cooling the Home

Heating the Home

With no centralized heating system available, winter meant enduring a house-full of freezing rooms. As a result, most everyone retreated to the comforting warmth of the kitchen, where the fireplace was stoked all day, making it a cozy refuge from the chill.

Elsewhere in the home, while a plentiful supply of wood burned in open hearth fireplaces, most of the heat generated from blazing logs went up the chimney rather into the living areas. Unless someone stood or sat near the hearth, even a roaring fire provided little warmth and rooms remained near freezing on the coldest days.

In the meantime, inventors and scientists in both Europe and America pondered this burning issue! Inspired by French heating scientist Nicolas Gauger, America's own ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, developed his famous Pennsylvania Fireplace. Constructed of cast iron panels, the "Franklin stove" actually heated a room because it circulated warm air. This stove could heat a room to about 50 degrees.

Attempts to provide central hot-air heating began in the late 18th century. By the early 19th century, Daniel Pettibone from Massachusetts perfected this system, which comprised a central boiler in the basement connected to ducts that ran to rooms.

Many inventors and engineers of the 17th century experimented with steam heat, but it took until 1860 for inventor Stephen J. Gold to develop the first steam system to use a radiator. Once manufacturers could churn out mass-produced radiators, steam heating became practical and affordable by the 1880s.

Central heating made warming the house cleaner and more efficient.

Heating and Cooling the Home

Fireplace Equipment, 1790-1810

Brass and iron

New York, New York

Benjamin Franklin introduced stoves of this type in the 1740s. He purposely designed an open firebox so that users could see the crackling, cozy fire, which seems to be a feature still enjoyed by many today.

Heating and Cooling the Home

Heating Stove, about 1815

Cast iron and brass

John Spencer and Co.

Albany, New York

4.27

Heating and Cooling the Home

Foot Warmer, 1780-1820

Walnut and tin

United States

To help keep the chill off, this small device was filled with coals and placed beneath the feet.

4.1

Heating and Cooling the Home

Warming Pan, 1790-1810

Brass and wood

The Netherlands

Beds were as cold as ice during the winter. A warming pan like this one, filled with coals and quickly passed between the sheets, drove away chill and dampness.

4.2

Heating and Cooling the Home

Heating Stove, 1836-1840

Cast and sheet iron with stamped brass

Attributed to Isaac Orr and Company

Washington, D.C.

Before central heating, enclosed stoves like this one provided the best means of warming a room. Some detractors, however, complained that enclosed stoves overheated rooms (though only to 50 degrees) and increased a person's vulnerability to colds.

Heating and Cooling the Home

Coal Bin, 1844-1850

Painted tin, cast iron, glass, porcelain and wood

England

Placed next to the fireplace or heating stove, this container held a ready supply of coal within the home. Usually an enclosed stove model was used for burning coal because of the soot and fumes it emitted. Cheap and in abundant supply, coal became the standard heating fuel in urban houses by the 1850s.

4.23

Heating and Cooling the Home

Radiator, 1910

Cast iron

American Radiator Company

Chicago, Illinois

The familiar cast iron radiator still can be found in many older homes today. These evenly, if not overly, heated a room.

4.21

Heating and Cooling the Home

Space Heater, 1895-1900

Cast iron, steel and wire

Gold Electric Heater Company

New York, New York

Electric heaters were among the earliest appliances. The coiled resistance wire (either an iron alloy or nickel) inside heated up as the electric current passed through it. This model could be easily moved from room to room on wheels. The aesthetic design, consisting of ornate seahorses, blended well with domestic décor.

4.5

Heating and Cooling the Home

Thermostat, 1912-1915

Cast and stamped brass, steel iron, glass, mercury, paper

Jewell Manufacturing Company

Auburn, New York

Efficiency and fuel savings were concerns for the early 20th century consumer just as they are for most of us today. Available since the late 19th century, regulating thermostats controlled heating cycles of the boiler. The user could set the clock to turn on heat at the preferred time of day.

4.4

Heating and Cooling the Home

Cooling the Home

No sweat! Electricity made cooling the house possible and convenient. The earliest electric appliance was the fan. Introduced in the 1890s, fans provided a cool breeze with the flip of a switch. Small motors made the electric fan practical.

Cooling rooms by mechanical means took inventors many years to perfect. Inventors needed to develop a refrigeration system that both cooled and dehumidified. Willis H. Carrier devised such a system in 1902 and applied it to a printing company in Brooklyn, New York. It wasn't until the 1920s, however, that the first household air conditioning units became available. Only after World War II did air conditioning become more common in the home.

Devising ways to keep food cold also kept inventors busy. Ice-cooled refrigerators commonly called iceboxes were available in the 1820s, but were not embraced by the general public because ice itself was so scarce and expensive at that time. Beginning in the 1850s, commercial harvesting of ice from ponds during the winter and storing it in ice houses made an icebox practical in the home. Iceboxes remained in use in some towns well into the mid-20th century.

Perfection of electric refrigeration in the early 20th century brought mechanical cooling to the kitchen. Cumbersome and expensive, only the wealthy could afford these early refrigerators. General Electric Company offered the first affordable model in 1927.

Heating and Cooling the Home

Gas Fan, 1900-1925 (with modern restoration)

Cast iron, aluminum and brass

Brockway and Phillips

Lincolnshire, England

In competition with electric companies, gas producers invented their own gas-powered appliances. A rubber hose, connected to a convenient gas chandelier or sconce, supplied power to run this fan.

4.6

Heating and Cooling the Home

Electric Fan, 1890s

Cast iron, steel, brass, copper wire

Edison Manufacturing Company

Orange, New Jersey

Early manufacturers like General Electric Company, Westinghouse and Emerson produced some of the earliest fans. Thomas Edison developed his own version. This model ran on batteries making it practical for consumers who had no electrical service.

4.7

Heating and Cooling the Home

Air Conditioner, 1938

Painted and chromium-plated steel

Johnson Outboard Motor Company

Galesburg, Illinois

The maker of these "space coolers" marketed them for use in both the home and on yachts. These freestanding air conditioners did not need to be placed in a window. Their costly price tag, however, kept them from being used by the average homeowner.

4.25

Heating and Cooling the Home

"A Guarantee of Lasting Satisfaction," 1908

McCray Refrigerator Company

Kendallville, Indiana

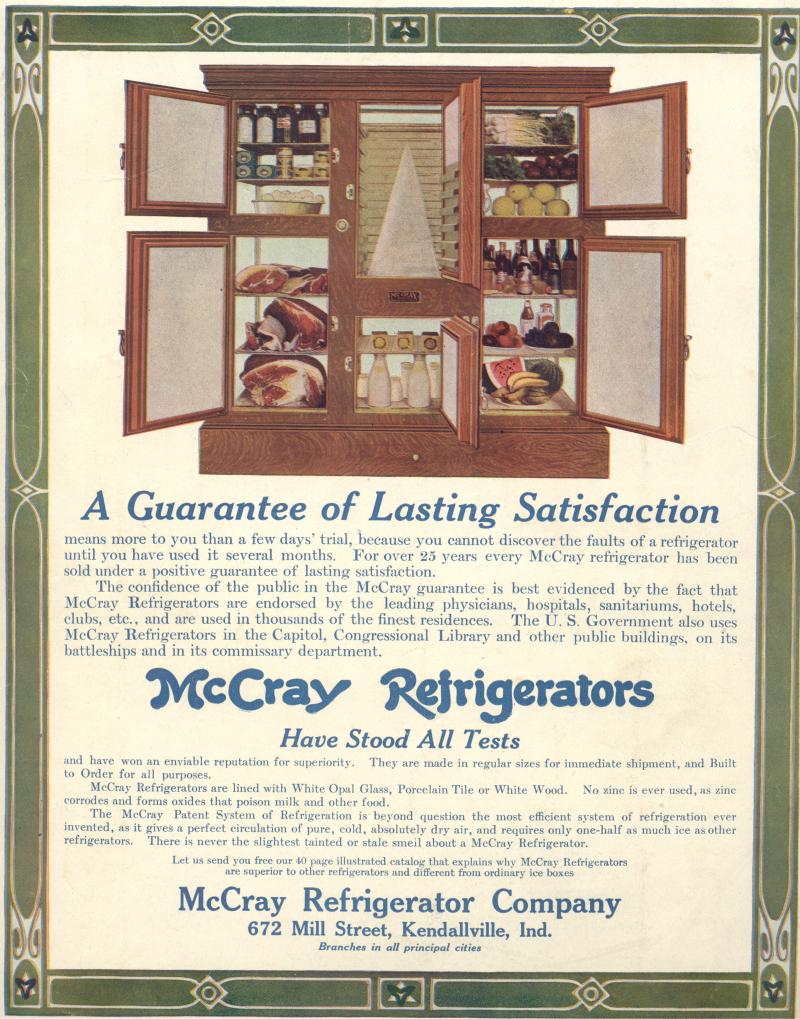

Iceboxes remained labor-intensive appliances since the ice compartment required daily draining. More perishable items, like meat and dairy, were placed closer to the ice. While this advertisement shows an elaborate multi-compartment model, most people chose the more affordable one- or two-compartment version.

3.32

Heating and Cooling the Home

Ice tongs, 1905-1920

Steel

Gifford-Wood Company

Hudson, New York

Placing a notice in the window asking for ice, summoned the iceman to the household's door. Using tongs like this one, he latched onto the large ice block and placed it in the icebox.

Heating and Cooling the Home

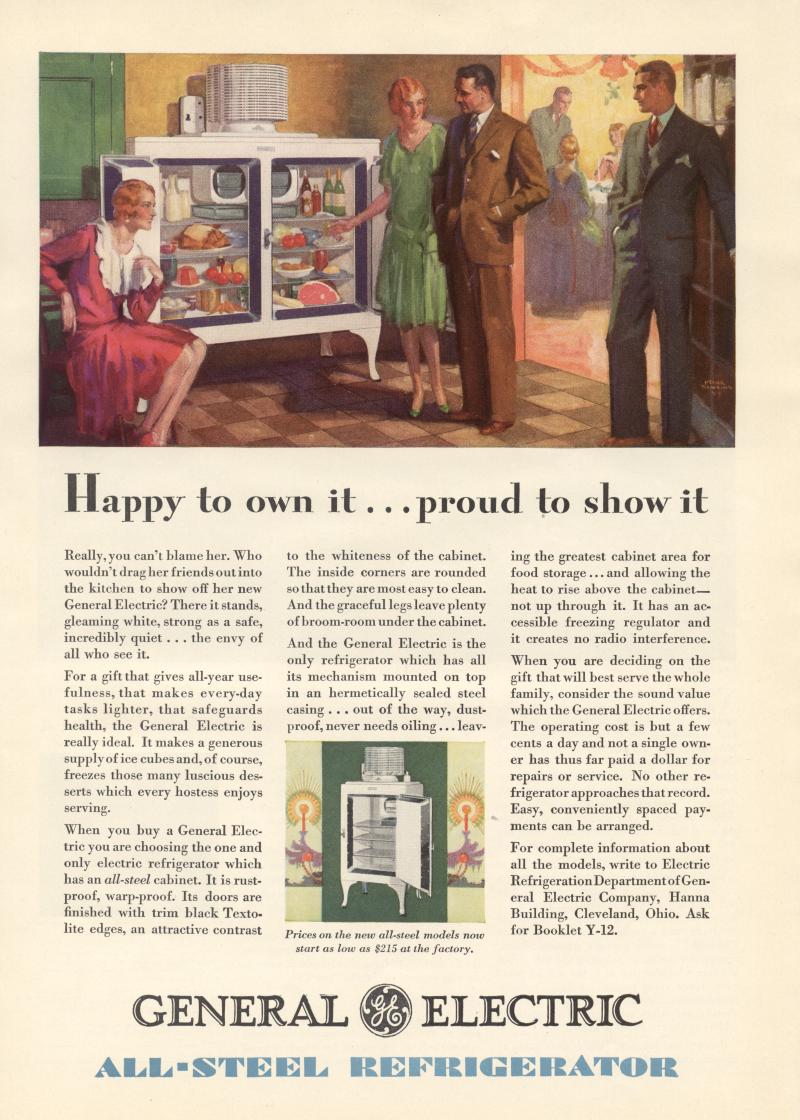

"Happy to own it...proud to show it," 1929

General Electric Company

"The envy of all who see it," touts this General Electric Company ad about its refrigerator. The sealed compressor on top ran quietly and could be controlled by the turn of a knob, allowing the lucky owner to store perishables longer. Iced drinks and desserts became popular with hostesses of the era. The iceman no longer paid a visit but the freezer did require periodic defrosting.

Communication and Entertainment

Communication

In the days before instant digital communication, contacting someone outside of the household usually required either taking a trip or writing a letter. Before the 19th century, a quill pen and bottle of ink would do for writing a letter. Later in the 19th century, metal-tipped pens, some with their own ink reservoir, made writing easier, but writing still could be messy.

The first practical typewriter was not introduced until 1874. Christopher Latham Sholes spent many years perfecting the mechanical writing machine. Originally marketed as an ornament in the parlor, the typewriter eventually revolutionized the office. Writers like Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain) bought one as did actress Fanny Kemble.

Alexander Graham Bell and Elisha Gray among others developed the telephone in 1876. The telephone became the most important means of long-distance communication for both home and office. Picking up the receiver and speaking the number required by the local operator brought unprecedented communication.

Communication and Entertainment

Pen, 1870-1880

Wood and gold-plated steel

P. P. Allen & Co.

New York, New York

Metal-nib pens, like the one seen here, were in common use since the early 19th century, having replaced feather quill pens. The user dipped the tip into a bottle of ink as needed. Until the early 20th century, most people wrote letters by hand.

5.1

Communication and Entertainment

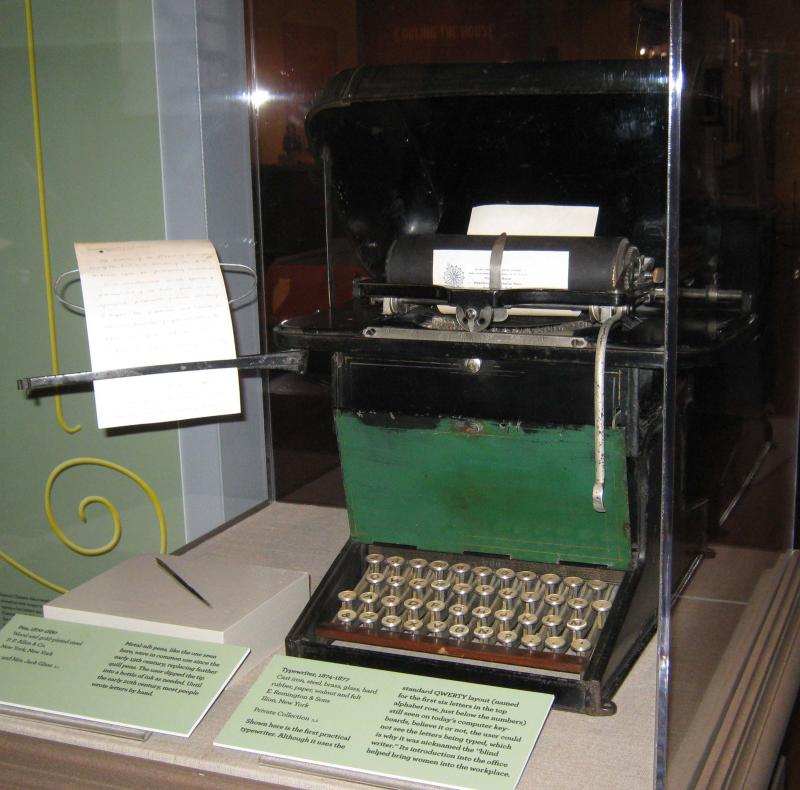

Typewriter, 1874-1877

Cast iron, steel, brass, glass, hard rubber, paper, walnut and felt

E. Remington & Sons

Ilion, New York

Shown here is the first practical typewriter. Although it uses the standard QWERTY layout (named for the first six letters in the top alphabet row, just below the numbers) still seen on today's computer keyboards, believe it or not, the user could not see the letters being typed, which is why it was nicknamed the "blind writer." Its introduction into the office helped bring women into the workplace because many were needed to operate the devices.

5.2

Communication and Entertainment

Telephone, 1899

Nickel-plated cast brass, steel, hard rubber and cloth-covered copper wire

Western Electric Company

New York, New York

Unlike a smartphone, this telephone was connected to the wall by a wire, just like many of the dwindling "land line" phones of today.

5.3

Communication and Entertainment

Optics

People have long been fascinated by visual tricks and optical illusions. Popular forms of entertainment in the 18th and 19th centuries included the perspective glass, magic lantern and camera obscura, but no video games!

Communication and Entertainment

Perspective Glass, 1790-1810

Mahogany with light wood inlay and glass

England

Known as a perspective glass, this instrument allowed the user to view images in 3-D. The user placed an engraved print below the angled mirror and viewed the reflected image through the magnifying lens creating the illusion of depth through heightened perspective.

5.4

Communication and Entertainment

Magic Lantern, 1900-1925

Painted tin, cast iron, brass and glass

Probably Europe

Maker unknown

A forerunner of the slide projector, magic lanterns became popular entertainment devices in the 18th century for showing all sorts of images—pictures of exotic lands, book illustrations, maps, animals, historical scenes—depicted on glass plates. They continued to be used into the early 20th century.

Communication and Entertainment

Music

Though mechanical musical boxes existed in the 19th century, music often meant listening to someone play an instrument in person. Music played an important entertainment role in the home before recorded and electronically transmitted sound. Homes at most social levels possessed some sort of musical instrument.

Musical entertainment became more convenient with the introduction of recorded sound and the record player. Thomas Edison perfected recorded sound in 1878. Emil Berliner patented recording on records in 1887. Another inventor, Eldridge Johnson founder of the Victor Talking Machine Company standardized the record so that it would turn 78 revolutions per minute. Records were easy to make and thus affordable.

Communication and Entertainment

Lap Organ, 1843

Maple, rosewood and pine with ivory, steel and reeds

Dearborn & Bartlett

Concord, New Hampshire

Called a lap organ, a musician played this unusual instrument by sitting down and resting it across the knees. Pumping the bellows forced air through reeds that made sound as the buttons were depressed. The shape and curve of the reeds inside determined the tone of this instrument.

5.5

Communication and Entertainment

Phonograph, 1917

Mahogany, mahogany veneer with pine secondary, steel, iron and brass

Edison Manufacturing Company

Orange, New Jersey

By simply winding the crank, the phonograph allowed people to listen to music whenever they wanted.

5.6

Communication and Entertainment

Phonograph Interior

This detail shows a record placed on the turntable ready to be played.

3.24

Communication and Entertainment

Electronic Age

The electronic age in the home began in the 1910s with the advent of radios. Early radios of the 1910s and early 1920s ran on crystal detectors. The crystal comprised a mineral powered by radio waves without the aid of electricity. The weak sound received by crystal radios limited their use to radio enthusiasts.

Vacuum tubes revolutionized radio receivers and transmitters. Introduced in the mid-1920s, vacuum tubes amplified broadcast reception via a speaker, which made listening to the radio convenient in the home. A state-of-the-art home of the 1920s featured a radio in the living room, around which family members gathered to listen to the latest music and entertainment.

Vacuum tubes also powered the first televisions. General Electric Company, RCA among others introduced the television in the 1930s. It found little practical use in the home since few TV broadcasting stations existed. At the 1939 World's Fair, TV took center stage in the RCA Hall of Television exhibition, where, according to a description on a postcard of the exhibit, complete television sending and receiving stations acquainted the visitor "with the marvels of televised images in an exhibit that is popularizing this new field of entertainment and education."

Communication and Entertainment

Radio and Speaker, 1928-1930

Walnut, walnut veneer over plywood, composition, woven textile, brass, Bakelite, steel, glass and copper wire

Radio Corporation of America

New York, New York

Anyone could operate this radio using the simple controls—power switch on the right, volume control on the left and the tuner in the middle. Earlier 1920s radios had many tuning knobs, but improvements in technology allowed a single tuning dial on this model

The long word "super-heterodyne" on the panel above the tuning knob was not just a sales gimmick to sound exotic. This technical term referred to the type of receiver placed inside that allowed frequency mixing or "heterodyning". For users this meant simplified controls (one tuning knob) and a more sensitive and selective radio. Most radio receivers today still use the superheterodyne principle.

Plugging the radio into an electric receptacle was a new concept. Batteries powered early 1920s radios and continued to do so where electricity was unavailable.

The top is opened to see the vacuum tubes inside, which look somewhat like light bulbs. Electricity powered the speaker, which allowed for greater volume control.

5.7

Communication and Entertainment

RCA Pavilion showing the TV at the 1939 World's Fair in New York

Visitors at the 1939 World's Fair surround a television at the RCA exhibit hall. The cabinet on one of the TRK-12 models was made of Lucite, DuPont's new transparent plastic that revealed all of the technical insides of the set. It was said that executives at RCA specifically created a see-through model at the Fair to demonstrate to skeptics that the picture tube was real and that television was not some sort of a hoax.

5.15

Communication and Entertainment

TRK-12 Television, 1939

Walnut, walnut veneer over plywood, Bakelite, steel, glass and copper wire

Radio Corporation of America

New York, New York

Many people got their first look at RCA's first television, the TRK-12, during the 1939 World's Fair, where it was among the most popular items in the company's impressive exhibit hall, which was shaped like a giant vacuum tube. The long picture tube meant that it had to be placed vertically in the cabinet. The mirror built into the lid allowed the picture to be seen by viewers, who, at that time, could enjoy only five channels. Even with those limited options and carrying a price-tag of $600 (the cost of a modest car at the time), it was the best-selling model of the four introduced at the Fair.

5.8

Communication and Entertainment

Conclusion

Today's conveniences would have delighted (and perhaps frightened) the housewife of yesteryear. So many automatic electric devices have replaced manual labor thereby making everyday living easier and speeding up the completion of tasks that once took days to accomplish.

It should be noted that the current website of a popular robotic vacuum cleaner states that its goal "is to simplify your cleaning routine, giving you back more time in your day," the exact same sentiment that advertisers used 100 years ago to pitch their latest and greatest "modern" devices!

In that regard, advertisers realize that even in the 21st century, after all of the inventions of the past, consumers still seek ease and efficiency in completing their chores. When it comes to meeting those desires, it seems that advertisers can forever keep recycling old slogans and an inventor's work is never finished.

And finally, with all of the automation of the last two centuries, "giving back more time in your day" has no doubt freed up more leisure time, but hasn't it also freed up more time for doing...more work?