October 5, 2012 - August 31, 2013

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Within the drastic shift from the bustle of the late 1880s to the flapper of the 1920s, smaller style changes constantly occurred. Just like today, random taste shifts changed year to year. But the overall trend was away from bulky layers and fussy details, and towards manageable, practical, streamlined outfits for modern women to engage in the activities of their more active lives.

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Evening Dress, 1888

Silk brocade, silk satin, silk chiffon, Brussels lace. Worn by Adelaide Frisbie Farman. This dress represents high fashion just before the emergence of the New Woman. The Victorian lady did not require comfort, but elegance. Her dresses were deliberately impractical, to show that she engaged in no useful or productive activity. Huge amounts of expensive fabrics signaled her status as a lady of leisure and taste. Gift of A. Newbold Richardson Dress Designed by Charles Frederick Worth, Paris

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Afternoon Dress, about 1890

Ribbed silk faille, figured silk, ostrich feathers, jet bead trim. The use of several heavy fabrics in different colors and textures and the large bustle, are typical of women’s fashions of the 1870s and 1880s, on the brink of the radical changes.

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Layers of Underwear, 1880s: Achieving the Right Shape

Many layers were required to achieve the well-upholstered look of the Victorian lady. Washable cotton next to the skin protected finer outer fabrics. Corsets, hoops, and bustles along with layers of petticoats created the fashionable shape.

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Tweed Day Dress, 1894-5

Wool tweed, silk crepe, silk velvet. The huge sleeves, ruffled bodice front, and wide skirt create an optical illusion, making the waist seem extra tiny. While this waist is quite small (21 1/2 inches) it is not out of proportion for the petite woman (about 5 feet) who wore it.

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Day Dress, 1893-95

Purple chartreuse and black figured silk; machine-made cotton net lace. The A-line skirt replaced cumbersome bustle skirts of previous decades, while sleeves went from tiny shoulder puffs in 1890 to huge “legs of mutton” in mid-decade. Gift of Ms. Charlotte Carman and Ms. Ann G. Peavey

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Day Dress, 1896

Roller printed cotton, silk twill; reproduction collar and belt. After 1895, enormous sleeves gave way to slightly tamed puffs by 1896, and continued to diminish until sleeves were entirely snug in 1899. Gift of Sue Butler

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Evening Dress (Back View), 1896-7

Brocaded silk chiffon over black silk, beaded net trim, silk satin ribbons, lace, ostrich feathers. Years after the bustle, dresses still had some fullness concentrated at the back. A slightly lowered neckline, sheer chiffon, and bows and feathers were appropriate for evening wear.

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Day Dress, 1900

Cotton lawn, velvet collar and cuffs, cotton net and tape lace trim. As the century turned, sleeves were completely fitted, and the new blousy draped bodice front would be popular for several years to come.

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

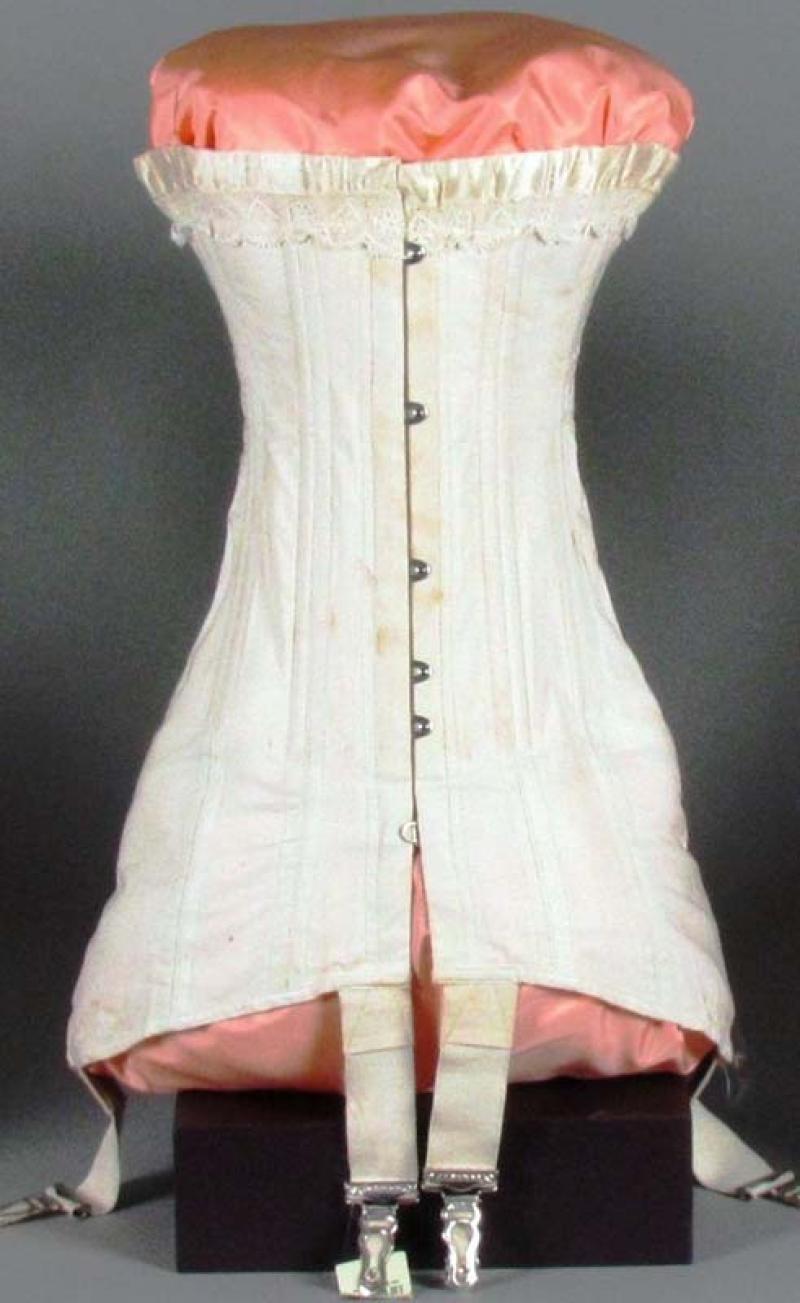

Corset, about 1900

Silk satin, net lace, silk grosgrain ribbon, metal boning and fastenings. Thrusting the bust forward and the behind back, the turn of the century corset created the sinuous “S-curve” silhouette that was then the ideal. This posture was more uncomfortable than corsets of most other periods. Courtesy of Mary Doering

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Evening Dress, about 1900-05

Cream silk chiffon over silk satin; tape lace, metallic mesh, sequins and spangles; replacement underskirt. Doucet was one of Paris’s leading couturiers. Sequins and metallic mesh (the skirt’s dark inserts were once shiny gold and silver) would have reflected candle, gas, or electric light of the evening setting. Label: Doucet, 21 Rue de la Paix, Paris

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Day Dress, 1903-04

Printed silk, silk chiffon, silk net, cotton lining; reproduction hat. The draped bodice and slightly bustled back of the skirt combine to form the “S-curve” silhouette popular at the turn of the century. “Bishop” sleeves, with their fullness below the elbow and above deep cuffs, have replaced the sleeves of the previous decade.

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Evening Dress, about 1900

Green ribbed silk, embroidered silk crepe, silk grosgrain ribbon, cotton lace. The low-cut neckline, heavy ribbed silk, metallic embroidery, and large panels of lace all proclaim this an evening dress. It has been remodeled around 1900 from an 1890s original design. DAR Museum Piece

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Tailored Suit, about 1905

Wool with soutache trim; cream silk faux vest with silk embroidery. By 1905, tailored suits were a required item in every woman’s wardrobe, worn for almost any daytime event. Many, like this one, softened the “mannish” style with details such as this example’s soutache (flat braid) trim and embroidery. Label: Jordan, New York; Friends of the Museum Purchase

Fashion Timeline 1888-1905

Dress, 1904-6

Pink taffeta, cotton lace insertion and replacement taffeta lining. Feminine, frothy dresses like this remained popular alongside newer tailored wardrobe options. The half-length, full sleeves and alternating vertical bands of lace and silk are typical details of the middle of this decade. Private Lender

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

The fashionable lady of the turn of the 20th century had many styles to choose from. Between following existing rules of occasion-specific dress (which dictated different styles for day and evening, at-home wear and different outings) and the new tailored styles and sports clothing, a woman could have quite a varied wardrobe. And of course, the dress or suit was just the beginning of an outfit. From society lady to factory "girl," every woman wore a hat, stockings, shoes, and gloves in all seasons. Parasols by day and fans at night were optional pleasures; jewelry was an indulgence affordable at every price point. Each type of accessory had its place in the hierarchy of material and style appropriate to a certain time of day or occasion.

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Brassiere, Patented 1907

Cotton with metal boning. Label: Spirella Styles. Early brassieres have a very different look from what we know as a bra. This style would have performed more like a corset in shaping the bust into the fashionable "mono-bosom" shape of the early 1900s. Friends of the Museum Purchase

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Afternoon Dress, 1907-8

Black silk faille, cream raw silk, net, black and white lace. From 1907-11, dresses with short sleeves over fitted, sheer, pleated ones, with sheer fabric at the neck, were all the rage. Enormous hats were popular until about 1912. Gift of Cricket Bauer Messman Hat courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Tailored Walking Suit, 1908

Wool herringbone twill. Towards the end of the decade, skirts were more slender and were often paired with long jackets. Tailored suits like this were an important feature of every woman's wardrobe by this time. Gift of Marjorie Fox

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Graduation Dress, 1909

Cotton lawn with machine embroidery and Valenciennes lace inserts. The white lawn "wash" (washable) dress embellished with pleats, embroidery, and lace was a summer favorite among younger women, often worn with colored slips. The "Princess line" panel at center front was popular about 1909-10. Gift of Mary Lou Niemants Hat courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum Coral necklace and pin, early 20th century

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Day Dress, about 1909-10

Blue silk, silk cord trim, cotton and metallic thread net. Label: E Wilson, Philadelphia. The raised "Empire" waist and slim silhouette were the new look at the turn of the decade. Sheer fabrics used at the neck were leading the way for daytime necklines that exposed the collarbone. Gift of Sarah Trayer

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Afternoon Dress, 1912-14

Blue and green silk satin, silk and metallic brocade trim Label: Bowman & Co., Harrisburg (Pennsylvania). In 1912, daytime dresses exposed the neck and collarbone for the first time in nearly a hundred years.

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Corset, early 1910s

Cream cotton, silk satin and cotton lace trim, elastic and metal garters. Label: W.T Corsets. Unnaturally small, this may be a store sample. The long, slim line of the early 1910s provided a smoothing effect under the slender silhouette. Friends of the Museum Purchase

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Suit, 1913-14

Wool houndstooth twill, cotton faille (ribbed plainweave). Label: Au Louvre, Paris. This jacket's cutaway style was a hot trend in 1913-14. At this time, skirts begin to reveal the ankles, which had to be covered by boots in daytime for several more years. Loan courtesy of: Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

"Russian" Suit, 1915-17

Wool flannel, fur trim, silk lining, synthetic (early plastic) buttons and belt buckles. In 1915, skirts shortened further and began to widen again. With its fur trim and off-center opening (taken from Russian folk shirts), this would have been called a "Russian" suit. Loan courtesy of: Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Summer Day Dress, 1915-17

Fuller, tiered skirts can't stop fashion from beginning to look quite modern. It was also becoming acceptable to wear pumps instead of boots, showing a glimpse of stocking.

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Evening Dress, 1916-18

Silk taffeta, silk crepe, lace, glass beads. Using several fabrics in contrasting colors and textures was typical of evening dress throughout the 1910s. Gift of Ellen Schwartz Roller and David S. Schwartz

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Wool Suit, about 1918

Wool, silk braid trim. Label: Bowman & Co., Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Courtesy of: Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum Hat, late 1910s, Friends of the Museum Purchase Reproduction dickey

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

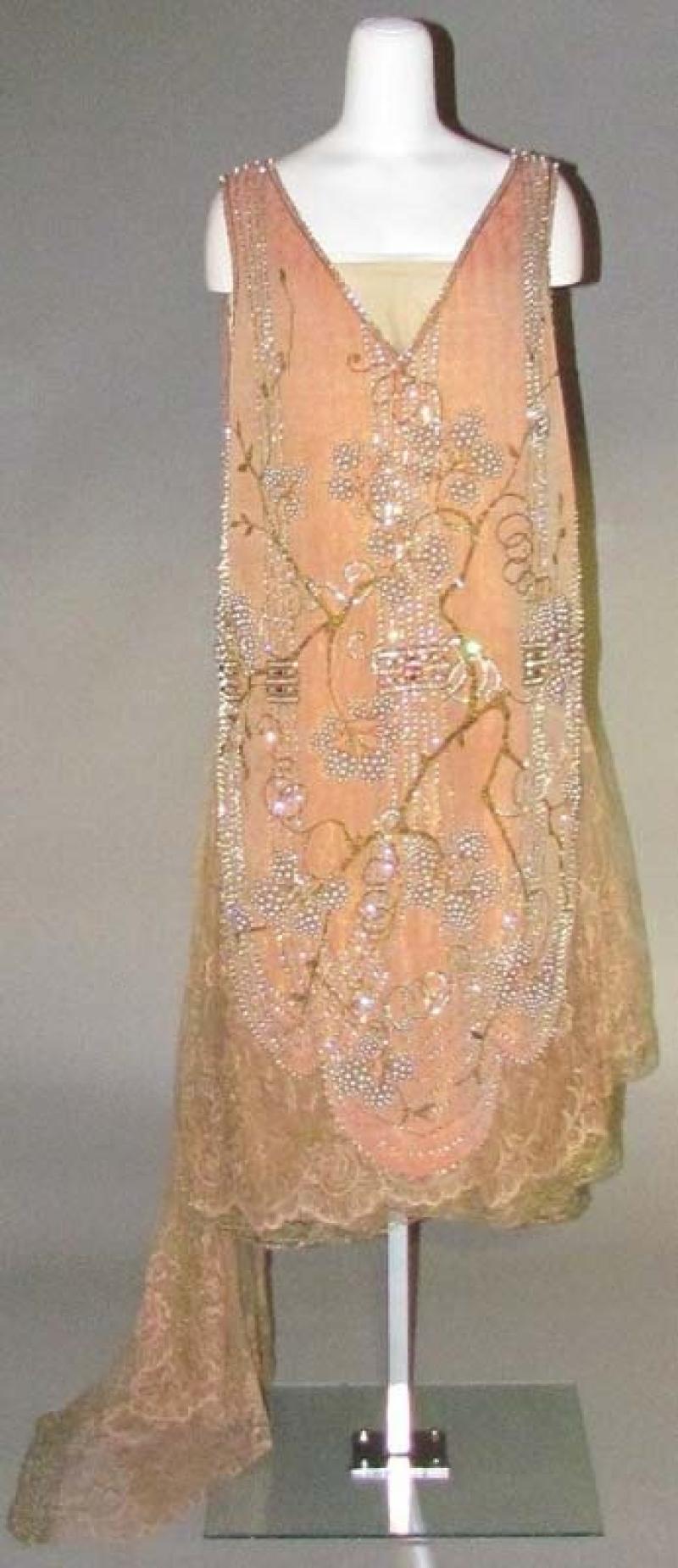

Evening Dress, 1925-26

Silk moiré, crepe, net, and lace; metallic lace; imitation pearl and rhinestone appliqué. Worn by Mrs. Anthony Wayne Cook, President General, NSDAR, 1923-26. The woman of the 1920s could achieve elegance without huge amounts of fabric hampering her movement. After decades of negotiation about what was proper, practical, and "attractive," women had finally entered a truly modern age for fashion.

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Green Silk "Envelope Chemise" or "Step-in" Slip

Most of the Victorian undergarments have been abandoned, and silks and colors have entered underwear. The fashionable "boyish" shape of the 1920s, which minimized female curves, was no more natural than the earlier corseted shapes. With a "good" figure, by the mid-20s, this might be all you needed under your dress. Most women's figures required some support and shaping to eliminate and smooth bust, hips, waist, and behind. This could be achieved to greater or lesser extent with a brassiere and the new hip-level corset. Loan courtesy of: Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Brassiere, 1920s

Silk, lace, metal boning. By the 1920s, brassieres had diminished in size from their earlier designs, and were often made in silk and lace. Friends of the Museum Purchase

Fashion Timeline 1905-1925

Day Dress, 1925-6

Printed silk velvet and cream silk faille top; ivory silk slip and black silk satin skirt; cotton grosgrain ribbon sash. We think of the 20s as the age of knee-length dresses, but early 20s styles were longer than those of the later years. Fabric manufacturers complained to designers about the shorter styles, as they used less fabric, and by 1929, designers would bring skirts back almost to ankle level. Nevertheless, simpler lines, fewer layers, and comfortable construction were more or less permanently part of women's fashion. Hat and shoes courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Energetically swinging a tennis racket, whacking a golf ball, or "wheeling" her bicycle down country lanes, the New Woman's subset, the "American Girl," was athletic, and required new or adapted clothes. Tennis, golf, and bicycling burst on the scene in the 1880s and 1890s, and offered active sports for men and women to enjoy in each other's company. The comfortable, popular shirtwaist outfit served well for tennis and golf, and less constricting corsets were marketed for sports activity. But more radical changes like trousers for riding bikes or horses, or form-fitting swimsuits that permitted swimming and not just a "dip," were slow to gain acceptance. It was still necessary for women to be "proper" and "attractive," and this sensibility tended to triumph over sense. Women entered white collar jobs in great numbers after 1880. Jobs involving new technologies—the telegraph and telephone, the stenography machine and typewriter—were soon dominated by women, largely because there was no history of men in those jobs for women to displace. Women's presence in the previously male office domain, caused anxiety and inspired criticism and caricature, but female white-collar workers only increased in number. From the late 1800s, increasing numbers of women attended colleges. At women's colleges especially, female students found not only the pleasure of intellectual studies, but the camaraderie of a community of women. As with any venture into previously male arenas, women attending college raised social anxieties about upsetting traditional gender roles. Many feared that education would make women less interested in marriage and children. Popular magazines published many articles reassuring readers that "college girls" were not overly studious, man-hating freaks, but "jolly," normal young women.

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

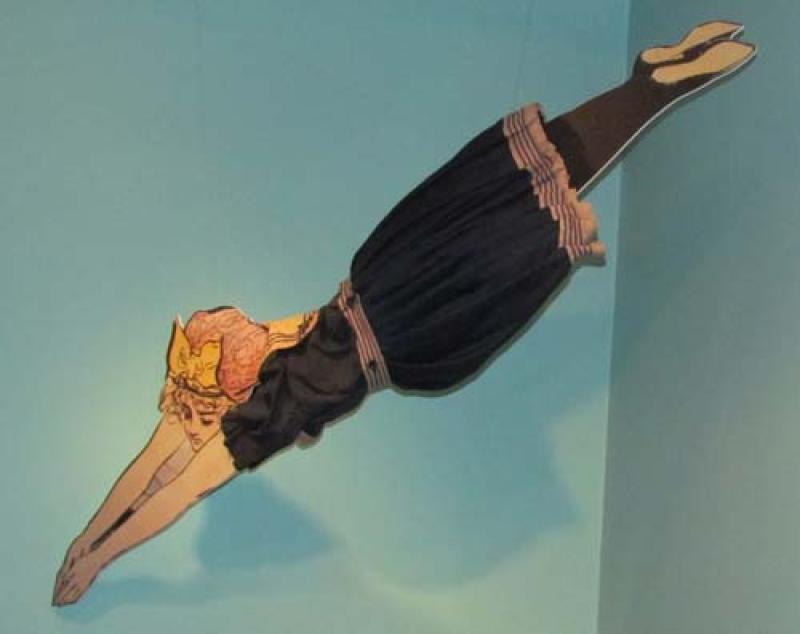

Bathing Costume, about 1905-10

Cotton, full-skirted tunics over "bloomer" pants were the basic components of bathing dress from the 1850s until well into the early 20th century. Body-hugging knit styles were slow to gain acceptance after their introduction around 1910. Friends of the Museum Purchase

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Golf Outfit, about 1908

The garish plaid, a reference to golf's Scottish origins, and a pocket in the skirt lining in the front at shin level (to hold a golf ball), identify this as a golf skirt. Often golf skirts were a few inches shorter than regular skirts; vests or jackets often were worn over the shirtwaist. Skirt, plaid wool twill; glazed cotton lining, Friends of the Museum Purchase. Sweater Vest, about 1900-05, machine knitted wool, courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum. Shirtwaist, early 1900s, courtesy of Linnard R. Hobler and Jean Maritz Hobler. Reproduction collar and tie

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Bicycle Outfit, 1890s

Divided or Trouser Skirt, Wool Twill. Since bicycle bloomers inspired ridicule and criticism, many women preferred full-cut "divided skirts" like this. In response to this fashion quandary, bike manufacturers designed women's bicycles without the crossbar, and protective covers for gears and wheel spokes, so women could wear skirts without fear of their catching in the wheels or gears. Gift of Becky Harlan. Cotton collar, about 1900; cotton shirtwaist, about 1900 and wool jacket, late 1890s, Friends of the Museum Purchase.

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Riding Habit with Breeches, about 1915

Wool twill, suede, oilcloth facing. Label: Bonwit Teller & Co., New York. Breeches permitted women to ride astride rather than side-saddle, as they had done for centuries. At first, only young girls were permitted to ride astride in breeches, but by the 1920s the new outfit and method were more widely accepted for adult women too. Habit and boots courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum Reproduction shirt dickey.

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Automobile Duster and Goggles, 1900-09

Linen with oilcloth trim. Goggles, leather with cotton binding; metal eyepieces with tinted glass; replacement ties. In the early years of the automobile, driving was as much a sport as it was transportation. Open cars required protective outerwear—a "duster" coat the color of the dust and mud sure to cling to the driver, goggles, and for ladies, hats firmly kept in place with long veils which kept dust off the face. Friends of the Museum Purchase. Shirtwaist courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum. Linen Skirt, DAR Museum

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Tailored Suit, about 1905

Cotton. Etiquette books and fashion magazines addressed appropriate office attire. Feminine frills were banned. Like the masculine-cut suits of women executives in the 1980s, the tailored suit was appropriate because it was masculine, like the domain in which it was worn. Note the watch pin on the lapel: lockets and watches suspended on decorative pins were popular at this time, and a watch would have been useful to an office worker. The watch is suspended upside-down so the wearer can read it. Private Lender Watch and pin courtesy of Michelle Mott Juehring Reproduction shirtwaist dickey

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Shirtwaist Ensemble, early 1900s

As common as jeans and a T-shirt today, the everyday outfit of the turn-of-the-century college "girl" was a skirt, conveniently shorter than then-current fashion dictated, and a shirtwaist. The boater hat, borrowed from menswear like the shirtwaist, was also popular. Cotton shirtwaist, about 1903-08, and boater hat, about 1900, courtesy Mary Doering Wool skirt, about 1904-08, courtesy Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum Boots, about 1910, gift of Ronnie Carpenter

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Sweater, mid-1890s

Wool with glass buttons, silk cord loops. Entirely new to women's wardrobes, the sweater was a casual garment worn for sports, "outings," and on campuses. Some college basketball teams wore sweaters with their bloomer pants. Loan courtesy of Historic Northampton (Massachusetts)

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Basketball or Gym Uniform, about 1900-10

Wool Twill. At the same time that bicycle bloomers were met with criticism, basketball or gym bloomers were acceptable because they were worn in the seclusion of a gymnasium, without male onlookers. Some college basketball teams paired the bloomers with sweaters instead of blouses. In either case, heavy wool was impractical: both hot and difficult to launder. Friends of the Museum Purchase. Basketball or sport shoes, canvas with rubber soles, about 1910, courtesy Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum. Reproduction shirt dickey, modern stockings

Women in the World: Sports, Office, College

Graduation Dress and Sash, 1894

Figured silk. White, long associated with youth and innocence, and with rites of passage like baptism and marriage, became standard for girls' graduations from grade schools, high schools, and eventually colleges. This dress was worn by Eva Brawley Dickson in 1894 for her graduation from coeducational Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania. Later that year she wore it as a wedding dress. Gift of Joan R. Gibson

Women in the World: Suffrage and WWI

October 5, 2012 - August 31, 2013 - During the years historians call the Progressive Era, American women took on many new roles and activities, and fashion had to follow. Active lives required practical clothes. This exhibit examines the changes in women’

Many women of the Progressive Era became involved in social reform in numerous areas, including temperance, suffrage, labor reform, civic improvement, civil rights, and other areas. Women justified leaving the domestic sphere where Victorian society said they belonged, by arguing that they could not raise healthy children or run safe households without the reforms they sought. Many facts of modern American life such as clean water, safe food, the 8-hour workday, and public libraries and playgrounds, were achieved in large part through the efforts of these women. When the United States entered the "Great War," or World War I, women were eager to answer the call to help in every capacity open to them. Some served in the military, others took over jobs left by men sent overseas, and hundreds of thousands volunteered their help with various organizations, one of the largest and most widespread being the American Red Cross. Some volunteer units permitted use of breeches, bloomers, or overall trousers—perhaps it took war work's urgency to trump old taboos.

Women in the World: Suffrage and WWI

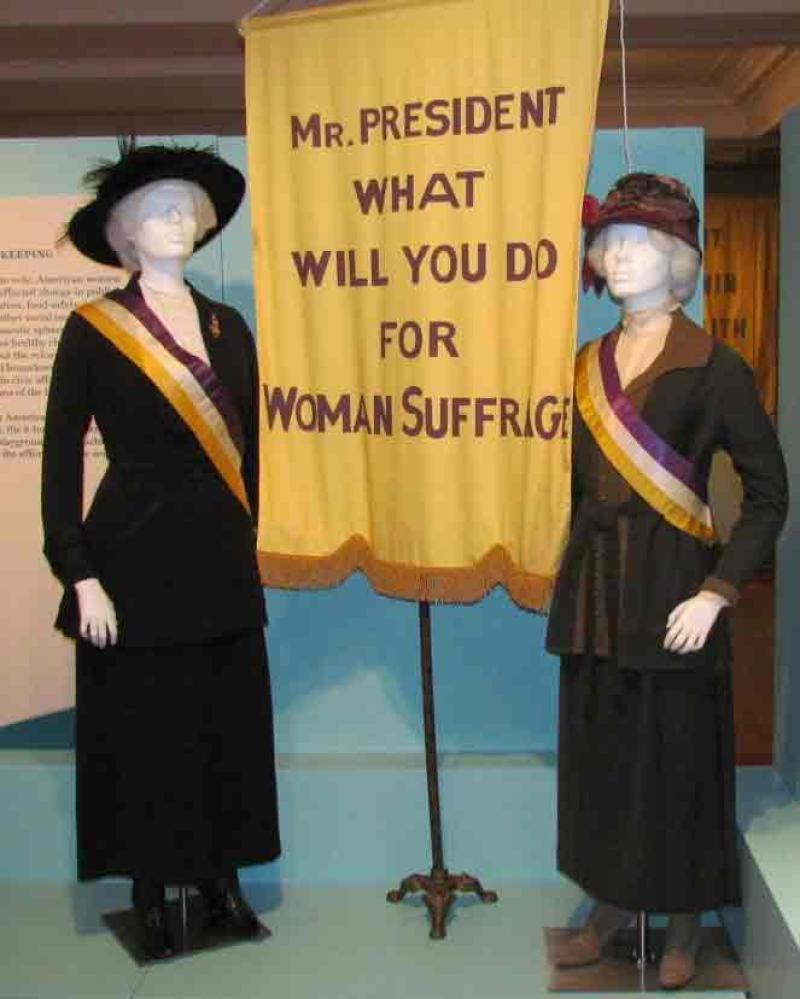

Suffragists

Of all the social reform issues "New Women" were involved in, perhaps the one most nearly touching their own rights was suffrage, or the vote. Members of the National Woman's Party held daily vigils in front of the White House in 1917-18, wearing sashes with the symbolic colors of the suffrage movement, and silently holding banners addressing President Wilson directly—considered a shocking departure from polite political behavior, especially for women. Suffragists endured police beatings, arrest, and force-feeding in prison. Suffrage Sashes, 1910s - Courtesy of the historic National Woman's Party, the Sewall-Belmont House & Museum, Washington, D.C. Reproduction Suffrage Banner - This banner is a reproduction of one of the banners carried in the White House vigils. See photos of the White House demonstrations here And search for suffrage banners used in demonstrations and parades here Right: Suit, 1918-19. Wool and wool knit. Label: The French Shop, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Hat, late 1910s. Left: Wool Suit, 1918-19. Wool, silk braid trim. Label: Bowman & Co., Harrisburg (Pennsylvania). Hat, late 1910s, Friends of the Museum Purchase 2004.17 Reproduction dickey Suits and right Hat courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum. Right Shirt courtesy of Linnard R. Hobler and Jean Maritz Hobler.

Women in the World: Suffrage and WWI

Cotton Shirtwaist, about 1900

The shirtwaist, based on men's shirts, appeared in women's fashion in the 1890s. The perfect complement to the new tailored suit and separates, it was available at every price, and soon was made with feminine touches like lace and embroidery. The shirtwaist was worn by college girls, office and factory workers, and for sports. Shirtwaists became symbols of the labor movement when shirtwaist factory workers led a strike of 20,000 employees in New York City in 1909, gaining reduced working hours (to 52 from 65 or more) and four holidays a year. In 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, in which 146 workers died, forever linked shirtwaists and the labor movement. The tragedy gave new momentum to efforts for improved workplace conditions. Courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum.

Women in the World: Suffrage and WWI

American Red Cross Workroom Service Uniform and Knitting Needles, 1917-18

The Red Cross coordinated volunteers under four areas of service: canteen, clerical, motor, and supply or "workroom," that is, helping prepare supplies like surgical dressings and bandages. Sarah Glover wore this coverall and "veil," as the uniform regulations called it, when volunteering during the War in Richmond, Virginia, preparing bandages and knitting for the troops. Knitting needles were provided, as the Red Cross had its own knitting patterns and sizing system. On the needles is a half-finished Red Cross design for fingerless gloves for sending to soldiers overseas. Courtesy of Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum Cotton seersucker skirt and cotton shirt, about 1917, DAR Museum Boots, 1910s, DAR Museum

Women in the World: Suffrage and WWI

American Red Cross Motor Corps Uniform: Skirt Suit, 1917-18

Wool twill, wool chevrons, metal buttons; cotton shirt. Suit label: Best & Co., New York. The Motor Corps volunteers could elect to wear breeches under the skirts of their suits, but some, according to surviving photos, wore breeches without the proper skirts over them. The wearer of this skirt suit apparently chose to wear only the skirt, as it lacks breeches. Motor corps volunteers, over 12,000 strong and almost entirely women, provided transportation support for hospitals, camps, and canteens. They also served in the influenza pandemic that followed the war in 1918.

Women in the World: Suffrage and WWI

American Red Cross Nurse’s Uniform, 1917-18

Cotton dress and apron. The Red Cross issued guidelines for uniforms, but each volunteer was responsible for providing her own. Inevitably, variations resulted. This example has a collar and cuffs of the same fabric as the dress, instead of prescribed white ones. Some nurses found the uniform "exceedingly ugly! It was designed by a man who believed that women working in the hospitals were a menace to the men patients...A man designed these things to make the women unattractive."—Lena Hitchcock, nurse serving in World War I.