The NSDAR Archives examines the lives and accomplishments of DAR members who helped lead the women of the United States from Seneca Falls, war work, and higher education to Progressive Era reform activities, unprecedented philanthropy, and, finally, the right to vote. See how DAR members Clara Barton, Susan B. Anthony, Jane Addams, and dozens of others displayed unrelenting bravery and determination as they worked to change the world forever.

Introduction

Seneca Falls

On July 19–20, 1848, what is believed to be the first women’s rights conference was held in Seneca Falls, New York. Approximately 300 men and women gathered to discuss the “condition of woman” and garner popular support for gender equality in the United States. The meeting was organized by local women along with reformer and women’s rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. “The First Wave” statue exhibit by sculptor Lloyd Lillie features bronze statues of the women who organized the 1848 Seneca Falls convention. The exhibit is located in the visitor center of the Women’s Rights National Historical Park, Seneca Falls, New York.

Introduction

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Chief among the accomplishments of the meeting was the drafting and signing of the Declaration of Sentiments, authored primarily by Mrs. Stanton, who modeled it on the Declaration of Independence.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton with her sons Daniel and Henry, 1848. (WikiCommons)

Introduction

Women's Education

Popular Victorian-era beliefs sought to discourage women from pursuing higher education for fear it would injure their reproductive organs and cause birth defects. It was thought also that a woman’s reproductive organs interfered with her ability to think clearly and, therefore, she was unable to participate in serious intellectual endeavors.

Opponents of higher education for women cited statistics warning that women who went to college were less likely to marry and, even if they did marry, did so later and had fewer children than uneducated women. This was attributed to the negative effects college had on women’s health instead of the more likely reason that some well-educated women were more apt to choose to dedicate their lives to a profession rather than direct their talents into taking care of a family.

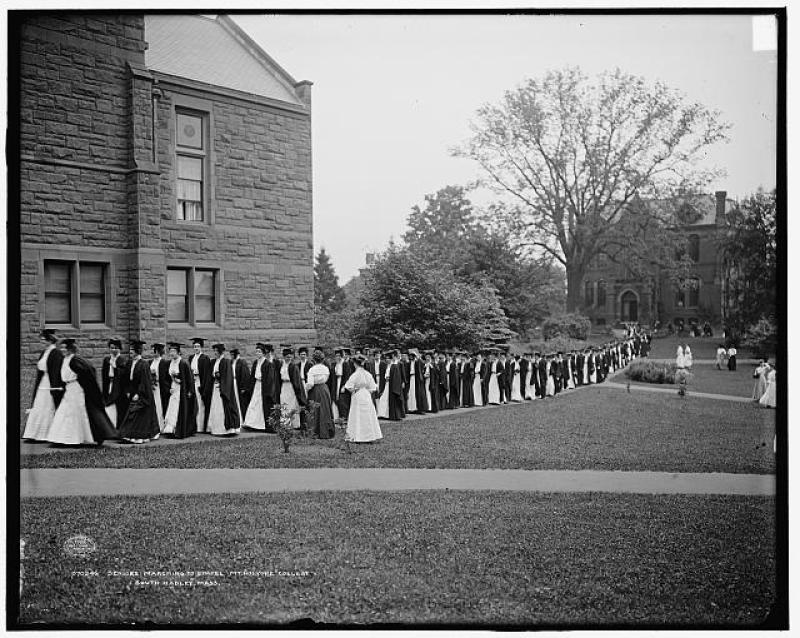

Despite popular resistance to the concept of women’s education, women, and the men who supported them, persevered. The second half of the 19th century marked the debut of several of the nation’s women’s colleges: Vassar, Smith, Wellesley, Simmons, Bryn Mawr, Radcliffe, and Mount Holyoke were all founded between 1861 and 1899.

Introduction

General Federation of Women's Clubs

In addition to attending college in higher numbers, some women also became involved in the women’s club movement. Women’s clubs raised funds for and spread awareness of the plight of schools, libraries, children’s concerns, and a variety of civil rights issues. The clubs allowed women, who had few political rights at the time, to provide greater influence in their communities.

Introduction

Mary Smith Lockwood

DAR Founder Mary Smith Lockwood was a prolific author and an avid promoter of the work of women’s clubs. She founded the famous Washington Travel Club and, for a time, served as president of the Women’s Press Club. Committed to the women’s suffrage movement, an acquaintance noted that Mrs. Lockwood “is friendly to all progressive movements, especially so in the progress of women.”

The Civil War Era

Civil War and Clara Barton

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 thoroughly interrupted any momentum the women’s rights movement had achieved up to that time. The preservation of the Union, the fate of slavery in America, and a long, painful Reconstruction period took precedence before the women’s rights movement was able recommence in earnest during the later years of the 19th century.

Although our focus is on women in the Progressive Era, doing justice to the lives and accomplishments of distinguished DAR members requires a bit of backtracking. Traditionally, wars have provided women with training and experience they may not have received otherwise. The American Civil War was no exception.

Much like what happened to labor in the U.S. during World War I and World War II, the growth of the armies during the Civil War created a manpower shortage. Women were called on not only to enter the civil service but also, in rural areas, to take over managing farms. Also, and even more important from a wartime perspective, women mobilized in an enormous effort to make sure military hospitals, especially those in the field, had adequate labor and supplies. Women made great inroads into the medical professions during the Civil War.

Clara Barton is best remembered for founding the American Red Cross in 1881; however, at the beginning of the Civil War, Miss Barton worked to obtain medical supplies to distribute to wounded soldiers. In July 1862, she was granted permission to travel behind army lines to care for the wounded.

The Civil War Era

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker

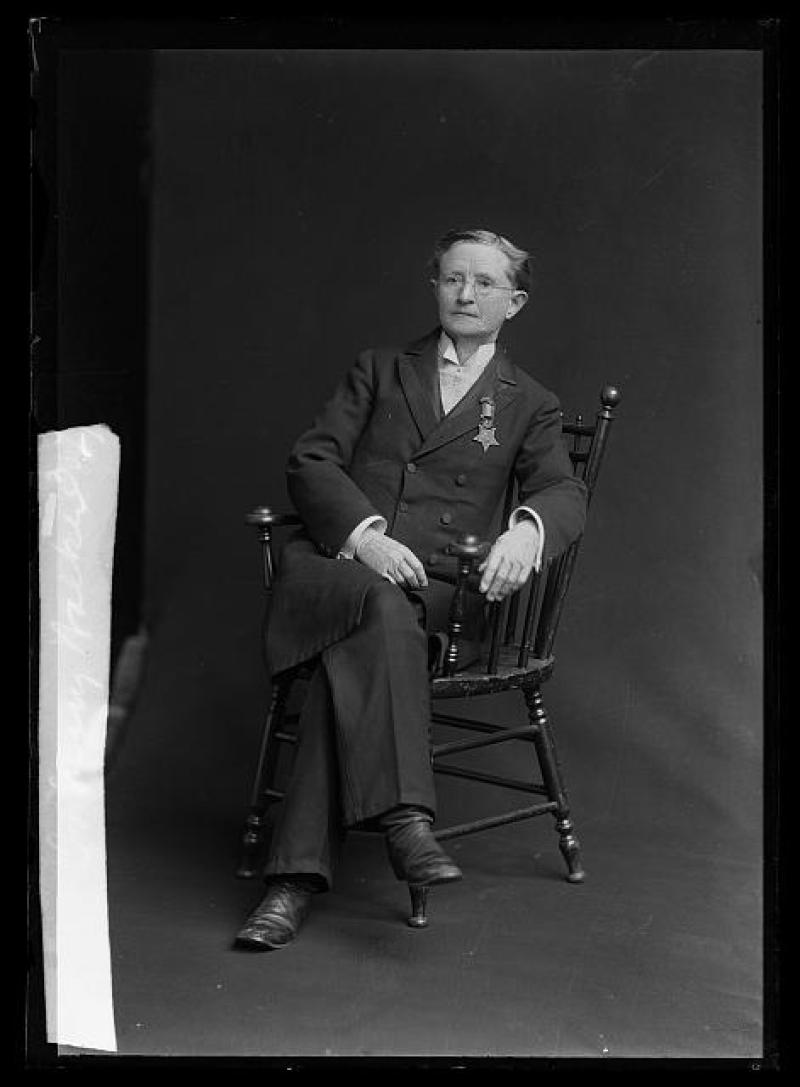

In 1863, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker became the first female U.S. army surgeon. After the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson awarded Dr. Walker the Medal of Honor in recognition of her “patriotism, bravery, and untiring services in attending the sick and wounded.” Dr. Walker was also an advocate for women’s rights, healthcare, and dress reform, which was reflected by her typical outfit consisting of a man’s suit and top hat.

The concept of dress reform was a natural result of women’s changing lives in the late 19th century. The new, active lifestyle many women were adopting required more practical clothing than was typical before the Progressive Era. Women involved in physically demanding reform activities such as war relief work, medicine, teaching, and public speaking demanded sensible, “rational” clothing that would not restrict movement.

The Civil War Era

Julia Ward Howe

In 1893, women’s rights advocate Julia Ward Howe gave a speech to a DAR chapter in Boston in which she discussed her work in the women’s rights movement. She said, in part, “I have often received such compliments as these: ‘Women generally do not think, do not reason, but you, Miss Julia, are an exception to the general rule.’ I have also heard again and again that women cannot work together—some man must always rule their organizations and keep them from quarreling; or, again, that women are incapable of thinking for themselves.”

Though she was both an abolitionist and a social reformer, Mrs. Howe was best known as a poet. She achieved lasting fame as the author of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The hymn, which she wrote in 1861, was published in the February 1862 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. Popular during the Civil War, it served as an anthem for the Union Army.

The Spanish-American War

USS Maine

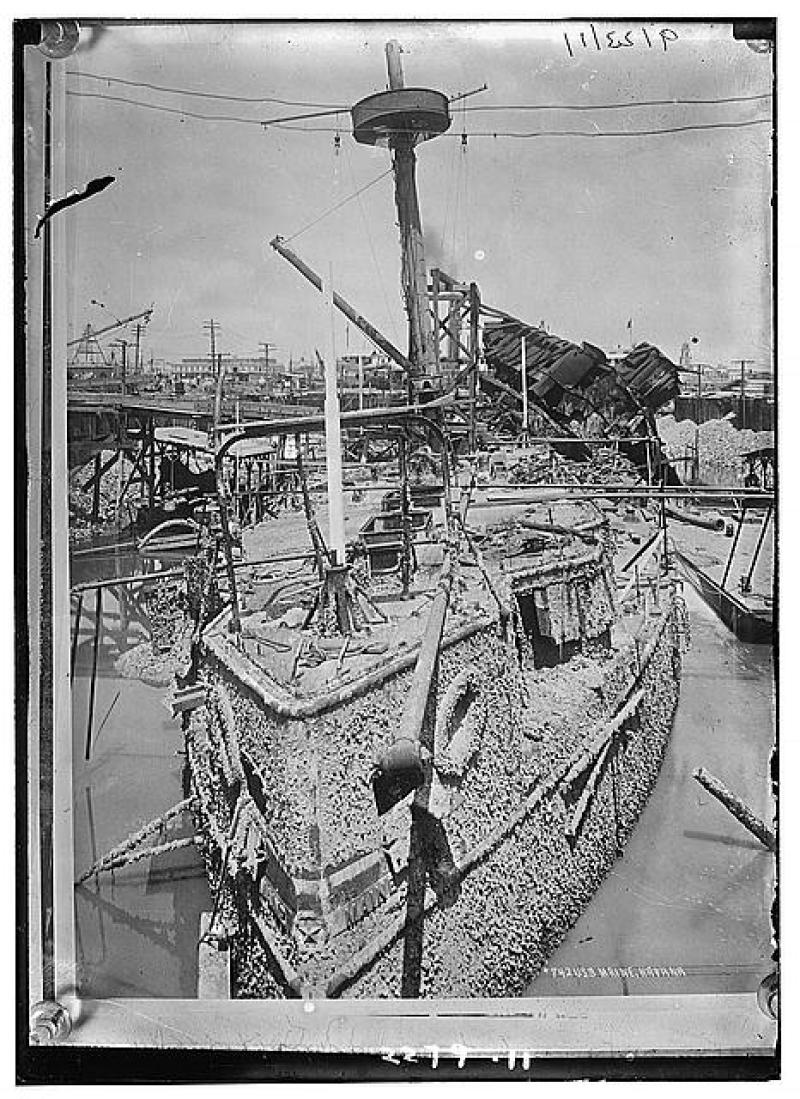

On February 15, 1898, the United States Navy armored cruiser USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor killing approximately 260 of the 355 sailors on board. The ship was on a mission to protect American citizens caught up in Cuba’s struggle for independence from Spain, which began in 1895. The sailors’ deaths greatly angered the American public. Although no one could prove Spain was behind the attack, U.S. newspapers captured the national mood with the slogan “Remember the ‘Maine,’ to hell with Spain!” Subsequently, Spain was unable to avoid war with the United States.

Although DAR had yet to reach its eighth birthday, the Spanish-American War represented the Society’s first chance to participate in a major war relief effort.

The Spanish-American War

Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee

Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee earned her medical degree in 1892 from what is now George Washington University and spent the next few years in private practice in Washington, D.C. When she learned that the federal government would add female nurses to their all-male nursing corps to serve during the Spanish-American War, she urged the U.S. surgeon general to employ only fully qualified nurses. She then persuaded DAR to establish a committee for the purpose of screening applicants for army nursing. The DAR Hospital Corps was born and its services accepted by the federal government. In 1901, Dr. McGee played a leading role in the founding of the Army Nurse Corps.

Dr. McGee’s parents and her husband, geologist and anthropologist William John McGee, encouraged her professional aspirations. The McGees welcomed three children between 1889 and 1902. At a time of increasing professional progress by women, Dr. McGee was proud to prove that a married woman could manage both domestic and public interests successfully.

The Spanish-American War

Mary Desha

In 1898, DAR Founder Mary Desha was appointed Assistant Director of the DAR Hospital Corps under Dr. McGee. In that capacity she helped process the applications of more than 4,500 women who aspired to serve as nurses in the Spanish-American War. She also took charge of supplying the 12 aprons that were provided to each nurse sent to the Army by direct endorsement of DAR.

She never missed a night of work during her entire five months with the Hospital Corps. Leaving her office every day at 4 p.m., Miss Desha worked in the Corps office every evening until midnight.

The Spanish-American War

Reubena Walworth

As director general of the Women’s National War Relief Association in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, DAR Founder Ellen Hardin Walworth was present at the field hospital at Fortress Monroe to meet the first wounded soldiers brought from Santiago. Her duties included assisting with the distribution of supplies and the management of the nursing staff. Her daughter, Reubena, fell ill and died while nursing the wounded in the hospitals at Montauk Point, New York.

Education and the Professions

Phoebe Hearst

By 1900 there were 85,000 women enrolled in more than 1,000 institutions of higher education in the United States. Although some women quit school to marry before finishing their degrees, many graduated and felt called to commit to a career. Women’s colleges founded after the Civil War helped to prepare women for leadership roles and provided a sense of personal power and acumen that gave them self-confidence as they pursued professional opportunities.

Only a relative few women earned a college education or otherwise obtained high-level, specialized training to help them overcome barriers to professional employment. Those who joined the ranks of physicians, lawyers, and college professors captured media attention as examples of the “new woman,” a term used to describe women who were challenging the traditional limits society placed on them during this time period.

The Progressive Era also saw much growth in the so-called “female professions,” including new fields such as library science, home economics, and social work. The female professions, however, did not pay well and were nearly devoid of the status conferred on male-dominated occupations.

Phoebe Apperson Hearst was not only the mother of the famous newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, but also a prolific philanthropist with a special interest in education. She is credited with founding the first free kindergarten in the United States, the National Cathedral School in Washington, D.C., and the National College of Mothers, which later became the National Parent Teacher Association (PTA). Appointed the first female Regent of the University of California, Mrs. Hearst served on its governing board from 1897 until her death in 1919. Beginning in 1891 she established scholarships for female students at the University of California, Berkeley.

Education and the Professions

Lucy Maynard Salmon

Lucy Maynard Salmon was already an accomplished historian when Vassar College hired her in 1887 to establish its history department. Miss Salmon rejected the traditional methods of teaching history, which emphasized memorizing facts, preferring that her students read primary sources and question scholarly authorities before coming to their own educated conclusions. Miss Salmon also appreciated the research value of less-than-traditional primary sources. She studied laundry lists to understand what they reveal about ordinary life and once wrote an essay using her backyard as a historical record.

Miss Salmon’s influence eventually extended well beyond Vassar. She was admitted to the American Historical Association in 1885 and in 1915 became the first woman elected to its Executive Council.

An active member of her community, Miss Salmon supported a variety of public education efforts and local suffrage organizations. She was a prolific writer who produced more than one dozen monographs and more than 100 essays and lectures. In 1926, Vassar alumnae established the Lucy Maynard Salmon Fund, which continues to support Vassar faculty research.

Education and the Professions

Belva Lockwood

After graduating from Genesee College in Lima, New York, in 1857, Belva Lockwood was a teacher in upstate New York until she moved to Washington, D.C., in 1866. She founded a school in Washington and taught there while simultaneously beginning her legal studies. The law schools at Georgetown University, Howard University, and what is now George Washington University all rejected her admission applications because she was a woman. Undaunted, she enrolled in the new National University Law School in 1871, graduated in 1873, and was admitted to the Washington, D.C., bar the same year. She also gained national recognition as a lecturer on women’s rights and was active in the women’s suffrage community as well. Mrs. Lockwood ran for U.S. president on the National Equal Rights Party ticket in 1884 and 1888.

Offended by the legal and economic discrimination against women in American society and inspired by meeting Susan B. Anthony, Belva Lockwood became one of the most effective advocates for women’s rights of her time. In 1872, a bill she drafted calling for equal pay for equal work for women in government employment became law. After being denied admission to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1876, she personally lobbied Congress for the required legislation. In March 1879 she became the first woman admitted to practice before the Supreme Court.

Education and the Professions

Caroline Maria Hewins

Caroline Maria Hewins, who served as head of the Hartford, Connecticut, public library for more than 50 years helped found the Connecticut Library Association in 1891. Miss Hewins is best remembered for her advocacy work on behalf of children’s books and children as readers. In 1900 she helped found the Children’s Section of the American Library Association. She was also the first woman to speak at an American Library Association conference.

In 1904 Miss Hewins opened one of the country’s first children’s rooms within a public library. It became a national model for children’s library services. Miss Hewins was both an innovator and a reformer. She opened the public library on Sundays better to serve working people and established some of the procedures that led to the modern branch library system. In recognition of her contributions she received an honorary Master of Arts degree from Trinity College, the first awarded to a woman.

Education and the Professions

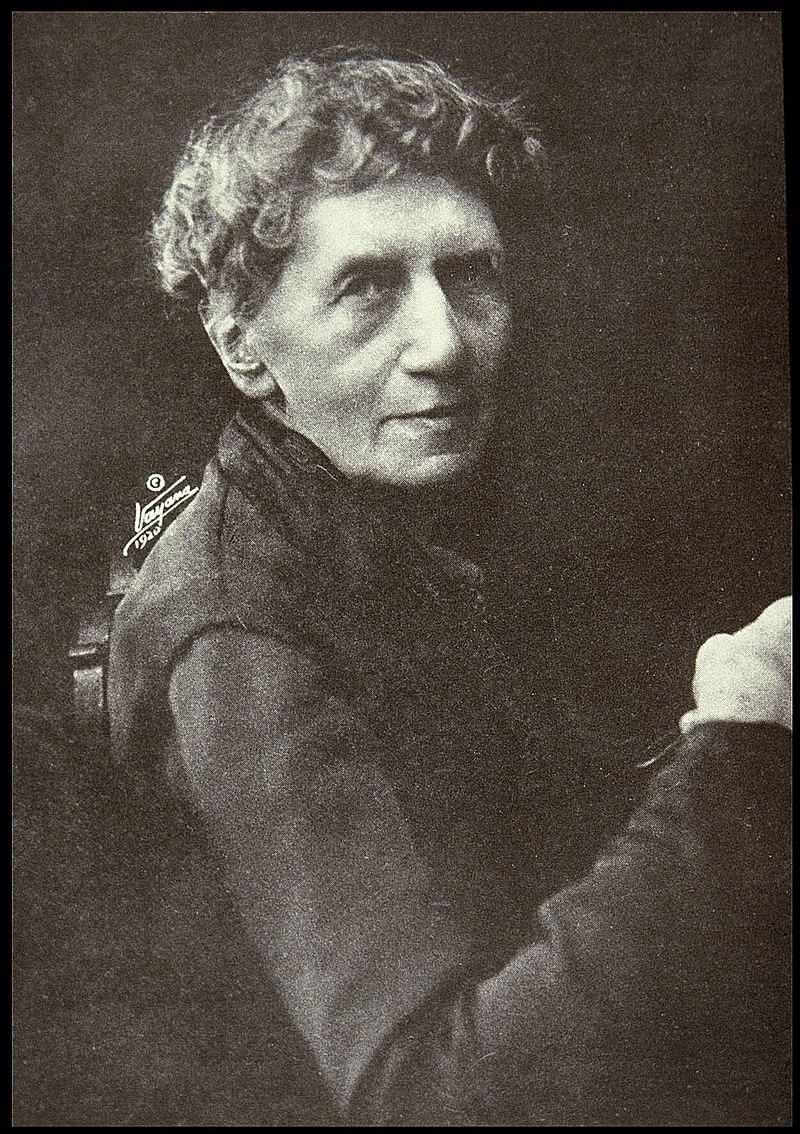

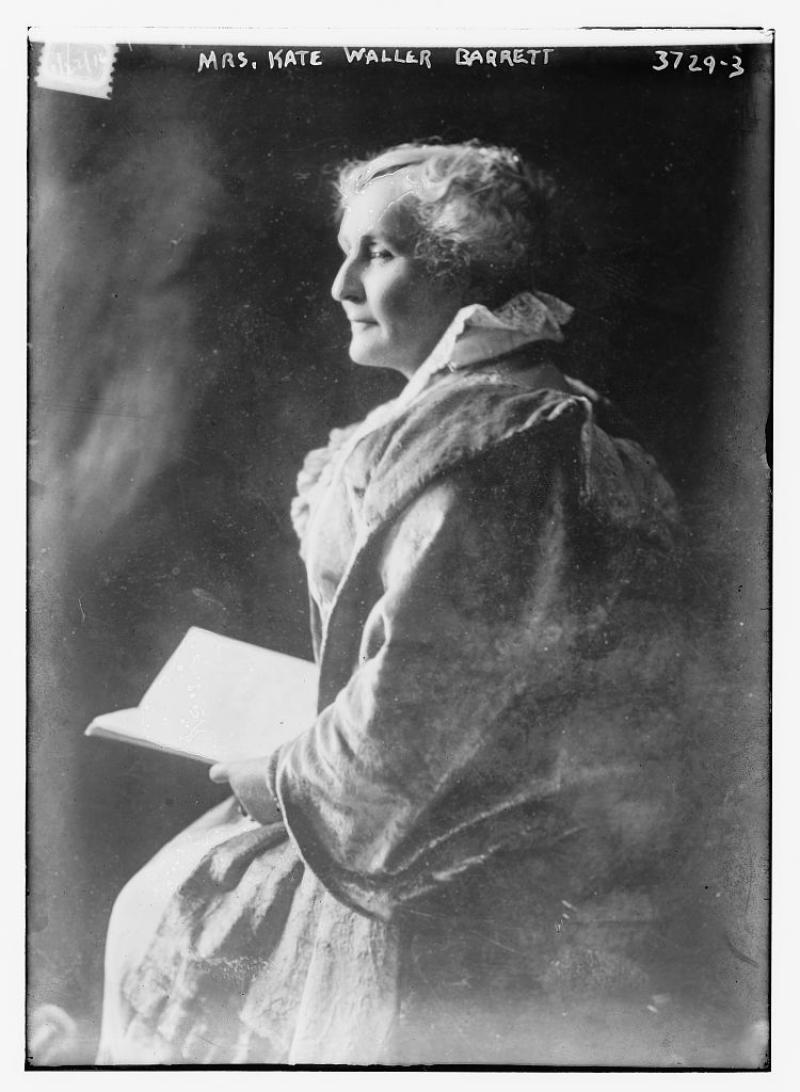

Dr. Kate Waller Barrett

Dr. Kate Waller Barrett earned her medical degree in 1892 from the Women’s Medical College of Georgia. In Atlanta in 1895 she co-founded the Florence Crittenton Mission which provided homes for unmarried, pregnant women. In 1903 Dr. Barrett received a congratulatory letter from President Theodore Roosevelt in which he stated that he could “conceive of no more worthy work than that of institutions such as the one under your management.”

Eloquent and outspoken about what she perceived as the unequal treatment of women in America, Dr. Barrett was appointed by President Woodrow Wilson to attend a meeting of the International Council of Women in 1914. She spoke so impressively at the Democratic National Convention in 1924 that a delegate nominated her to be vice president of the United States. The Virginia native’s life and work are honored throughout the state. An elementary school, a college dormitory, a DAR chapter, and a branch of the Alexandria Public Library are all named in her honor. Dr. Barrett’s death in 1925 marked the first time that the Commonwealth of Virginia ordered the American flag flown at half-staff in honor of a woman.

Education and the Professions

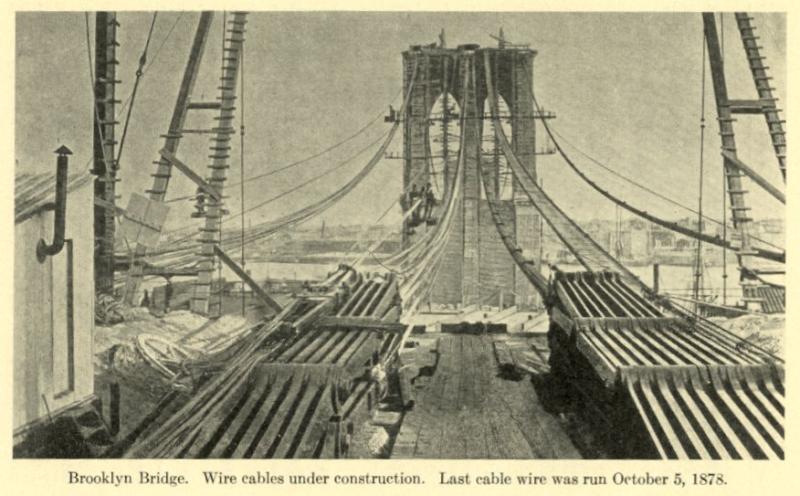

Emily Warren Roebling

The Brooklyn Bridge officially opened to traffic on May 24, 1883, after 13 years of construction. Emily Warren Roebling’s husband, Washington Roebling, served as chief engineer during the bridge’s construction. Already interested in the project and well informed regarding its progress, Mrs. Roebling quickly assumed most of the chief engineer’s duties including daily project management and worker supervision when her husband suddenly became ill. She was the first person to cross the bridge by carriage in advance of the official opening.

At the opening ceremony, Mrs. Roebling was honored in a speech by New York Congressman Abram Stevens Hewitt, who called the bridge “an everlasting monument to the sacrificing devotion of a woman and of her capacity for that higher education from which she has been too long disbarred.”

Health and Safety Reform

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

America paid a high price for industrial supremacy at the turn of the 20th century as industrial accidents killed 35,000 workers each year and maimed 500,000 others. Only when 146 workers, mostly young women, died in a single fire on March 25, 1911, at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City did the public demand change, however.

Health and Safety Reform

Albion Fellows Bacon

At the beginning of the 20th century, Albion Fellows Bacon was one of many citizens concerned about how industrialization and urbanization were affecting living conditions for poor and working-class people. She was instrumental in the passage of housing legislation in Indiana in 1909, 1913, and 1917. The 1917 law was particularly important as it allowed for condemning unsafe and unsanitary housing. She eventually earned a national reputation that resulted in her appointment to the President's Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership. By the 1930s Mrs. Bacon had made several trips to Washington, D.C., to attend meetings and make conference presentations.

She is the namesake of Albion Flats, a block of apartments in Evansville, Indiana, built in 1911 in an attempt to improve crowded living conditions for the working class and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. The Albion Fellows Bacon Center, a domestic violence shelter for women and their children in Evansville, Indiana, is also named in her honor.

Health and Safety Reform

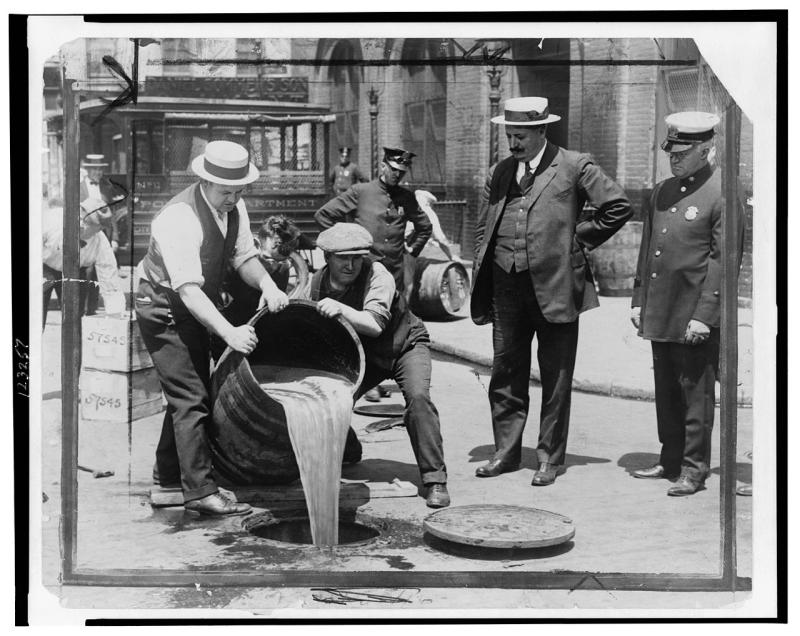

Prohibition

Offended or frightened by common assumptions regarding ill-mannered drunkards, some reformers embraced prohibition as a means of calming fears of social disorder by keeping poor or working-class men sober, self-disciplined, and on time for work. Social control was, of course, not the whole story of prohibition. Other, more compelling arguments against alcohol were voiced, especially by small business owners and women. Small towns resented the incursion of bars franchised by national breweries and wives who were economically dependent on their husbands needed sober and nonviolent breadwinners.

Health and Safety Reform

Frances Willard

When Frances Willard, president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), swept through the Southern states on a speaking tour in the 1880s, women flocked to her lectures. Miss Willard, far from dismissing domestic ideals of womanhood, insisted on the interdependence of both private and public life. A woman of great faith, Miss Willard said she was inspired to support women’s suffrage during a conversion experience that occurred while she was preparing a temperance lecture. For Miss Willard, temperance and women’s suffrage were well paired. She reasoned that allowing women to vote would increase electoral support for prohibition legislation and enable women’s redemptive influence to suffuse the entire society.

Today, in a lasting tribute to her efforts as a social reformer, a statue of Frances Willard stands in the U.S. Capitol as part of the National Statuary Hall Collection. She was the first woman to be so honored.

Health and Safety Reform

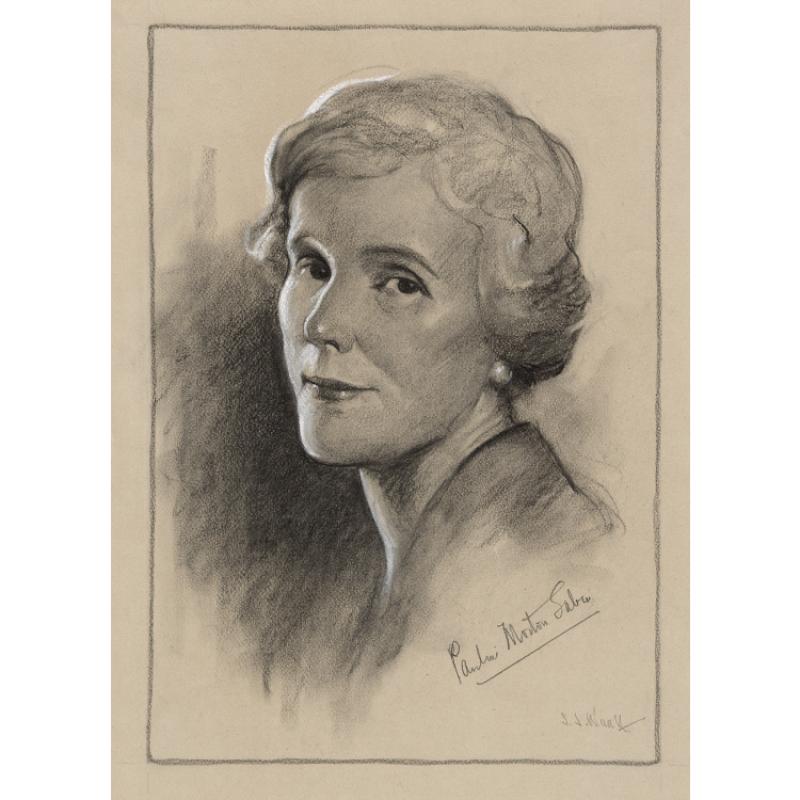

Pauline Morton Sabin Davis

Pauline Morton Sabin Davis was a prominent leader in the movement to repeal prohibition. She was appalled by the crime and lawlessness that had flourished since 1919, when the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution banned alcohol. Her main concern was the corruption of children and family life. In 1929, Mrs. Davis founded the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR) to challenge the long-held assumption that all American women supported prohibition. An excellent political fundraiser and a skilled organizer, Mrs. Davis promoted her message relentlessly. Within a few years the WONPR grew into the largest anti-prohibition organization in the country with 1.5 million members.

Philanthropy and the Arts

Gilded Age

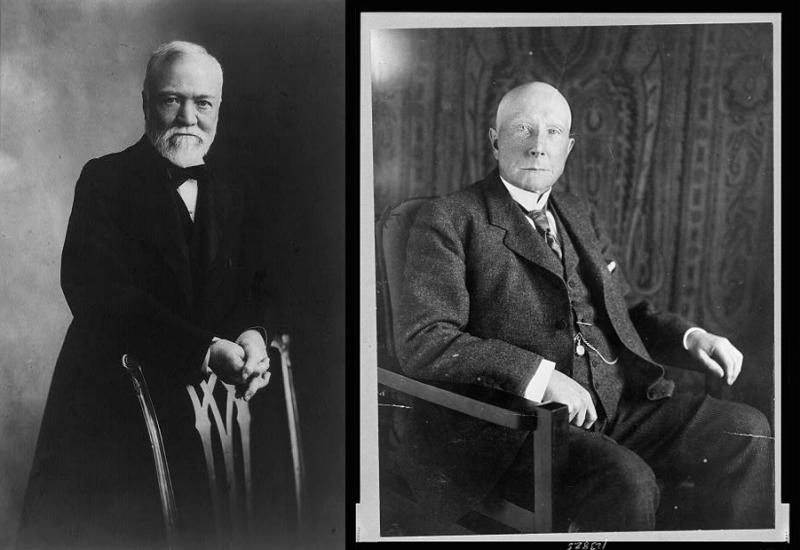

The Gilded Age was an era of rapid economic growth in the United States. Because American wages were much higher than those in Europe, especially for skilled workers, the U.S. experienced an influx of millions of European immigrants searching for work. The Gilded Age was also an era of abject poverty, however, as concentration of great wealth in the hands of a relative few citizens became more pronounced and visible. Many subscribed to Andrew Carnegie’s philosophy, outlined in The Gospel of Wealth, which admonished the rich to engage enthusiastically in philanthropic giving to colleges, hospitals, medical research, libraries, museums, and social betterment. In addition to Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, Andrew W. Mellon, and John D. Rockefeller all made philanthropy an important part of their lives and businesses.

The Progressive Era brought with it an increasingly popular belief that art museums, theater, and other outlets of creative expression should be available to everyone, not reserved only for the rich to enjoy. Initially, women involved in the art world ceded leadership tasks to men. After about 1900, however, they pushed to the front of the museum world led by Isabella Stewart Gardner, and later Abigail Eldridge Rockefeller and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. All of these women assembled massive art collections and arranged for them to be housed in major museums.

Philanthropy and the Arts

Gertrude Whitney

Sculptor Gertrude Whitney was a member of the wealthy and well-established Vanderbilt family. She studied in New York City at the Art Students League and in Paris with Auguste Rodin. The human figure was Mrs. Whitney’s favorite medium through which to demonstrate the range of human emotions and ideals. Some of her most well-known works include the Titanic Memorial in Washington, D.C., and the Christopher Columbus monument in the port of Palos, Spain. Mrs. Whitney also sculpted the graceful memorial to DAR’s four founders located here at NSDAR Headquarters. In 1931 she established the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City as a lasting legacy to her support for the growing alliance between new, contemporary art and established privilege.

Philanthropy and the Arts

Isabel Weld Anderson

Descended from wealthy Boston Brahmins on both sides of her family, Isabel Weld Anderson was an author and philanthropist. In 1897 she married diplomat Larz Anderson. A prolific writer, Mrs. Anderson penned a number of travelogues, poems, and children’s stories. Her extensive works about her family history are of particular value to Boston historians. During World War I, Mrs. Anderson worked overseas as a Red Cross nurse. She was awarded the American Red Cross Service Medal for her efforts. The couple used Anderson House mansion, located at Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C., as a winter residence during their marriage. After Mr. Anderson died in 1937, Mrs. Anderson gave the home to the Society of the Cincinnati which still uses the property as its national headquarters and museum.

Philanthropy and the Arts

Hull House

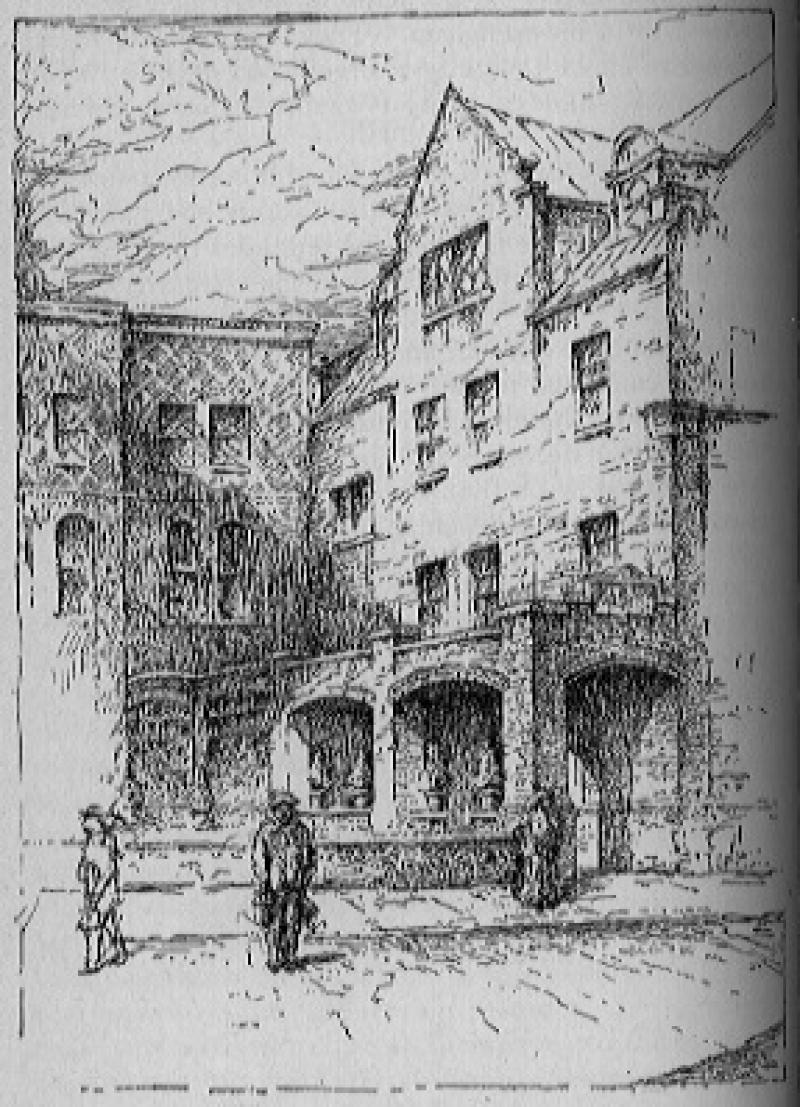

The settlement movement began officially in the U.S. in 1886 with the establishment of University Settlement in New York City. A “settlement house” was an institution in an inner city area that provided educational, recreational, and other social services to underprivileged communities. Settlement houses offered lectures, classes, plays, pageants, kindergartens, and childcare. Volunteer, middle-class “settlement workers” lived onsite, sharing knowledge and culture with, and alleviating the poverty of, their low-income neighbors.

In 1889, Ellen Gates Starr and Jane Addams established the most well-known of the settlement houses, Hull House, in Chicago. Named for its original occupant, Hull House was “a fine old house standing well back from the street.” With its innovative social, educational, and artistic programs, Hull House became the standard bearer for the movement that had grown to almost 500 settlement houses nationally by 1920.

Philanthropy and the Arts

Jane Addams

In addition to her dedication to Hull House and her life as a social worker, Miss Addams became a committed pacifist in the years leading up to World War I and helped to found the Woman’s Peace Party. She co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920. As a result of her work, Miss Addams received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. She was the first American woman to receive the honor.

Philanthropy and the Arts

Marjorie Merriweather Post

Marjorie Merriweather Post was a notable businesswoman, philanthropist, art collector, patron of the arts, and socialite. Her father, Charles William “C.W.” Post, taught her every aspect of running his Postum Cereal Company. After his death, the 27-year-old heiress took over the company, her vision and management skills aiding in the creation of the General Foods Corporation. Throughout her life she was linked to many charitable organizations, such as the Salvation Army and the National Symphonic Orchestra. Ms. Post acquired an extensive collection of French and Russian decorative arts. Her collection of Russian Imperial art is considered to be one of the finest outside of Russia. She left her Hillwood Estate in Washington, D.C., to the public. The property now serves as a museum.

Philanthropy and the Arts

Lillian Gish

Millions of young, unmarried workers achieved a new sense of liberation as patrons of commercial amusements during the Progressive Era. Reformers had great hopes for the power of movies. In 1916, a spokeswoman for the General Federation of Women’s Clubs predicted that the cinema would be a “grand social worker” that would keep male workers out of bars and away from alcohol so they could take their families to the movies.

Often referred to as the first lady of the silent screen, actor Lillian Gish was born in 1893 and appeared in her final film in 1987. Her career encompassed silent films, stage plays, and modern movies. In 1971 Miss Gish received a Special Academy Award for “superlative artistry and distinguished contribution to the progress of the motion picture.” She also received an American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement Award in 1984.

In the sense that she pioneered what have become important standard acting techniques, Miss Gish was arguably the movie industry’s first true actor. She is believed to be the first actor to recognize that there are critical differences between acting for the stage and acting for the screen. She once summarized her career goals by remarking: “In the theater I played with the best actors and tried never to get caught acting. I was never interested in money. ... I just wanted films I’d be proud of because I felt they were permanent and I didn’t want to apologize for any of them.”

Women's Suffrage

Women's suffrage background

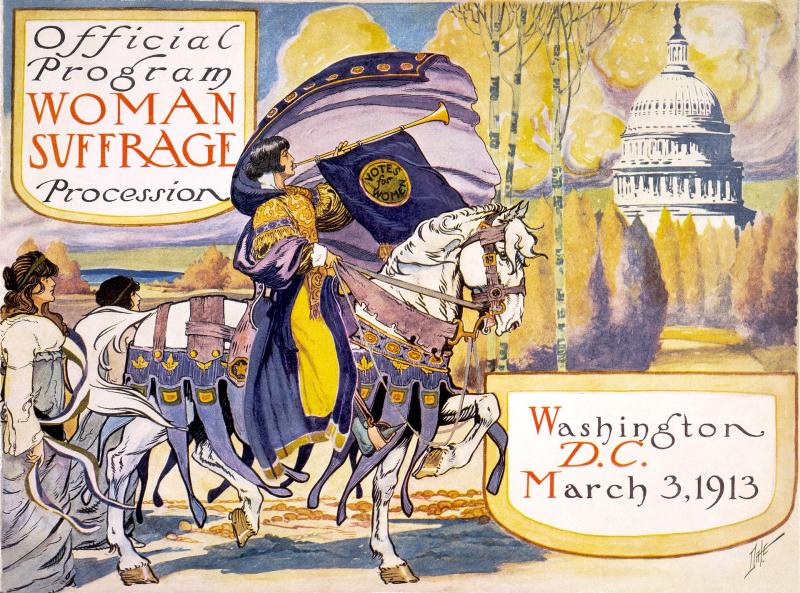

American women’s World War I relief work contributed greatly to the forward momentum that finally culminated in suffrage rights. President Wilson endorsed a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage in 1918; however, anti-suffrage interests were able to block the amendment in the U.S. Senate that year. Congress passed the measure in 1919 and by August 1920, three-quarters of the states had given the 19th Amendment the approval necessary for ratification.

The 1920 presidential election marked the first time in American history that women were able to vote legally throughout the nation. Previously, a few states gave women partial or full voting rights. The West established a tradition of female enfranchisement as one way of encouraging women to immigrate to the sparsely settled and disproportionately male society on the frontier. The Wyoming Territory was first to give women the right to vote in 1869.

An arduous road was traveled between the movement’s “official” beginning at Seneca Falls in 1848 to victory in the form of the 19th Amendment in 1920. The women’s rights proponents’ passion and fearless determination cannot be overestimated; however, it was the activists’ persistent, indefatigable organizational skills that finally won the day.

Suffragists found encouragement in the more favorable political climate of the 1910s, a decade of widespread progressive reforms including enfranchisement for women in an increasing number of states. The resulting momentum rejuvenated widespread support for the 19th Amendment. Suffragist leaders took innovative action to achieve results. They launched door-to-door campaigns in poor and working-class neighborhoods as well as in middle- and upper-class suburbs. Some activists also took the unprecedented step—for women—of speaking publicly on street corners. They lobbied state legislatures and, ultimately, the national government. By 1914, the suffrage movement consumed the energy of hundreds of thousands of women and their male allies.

Women's Suffrage

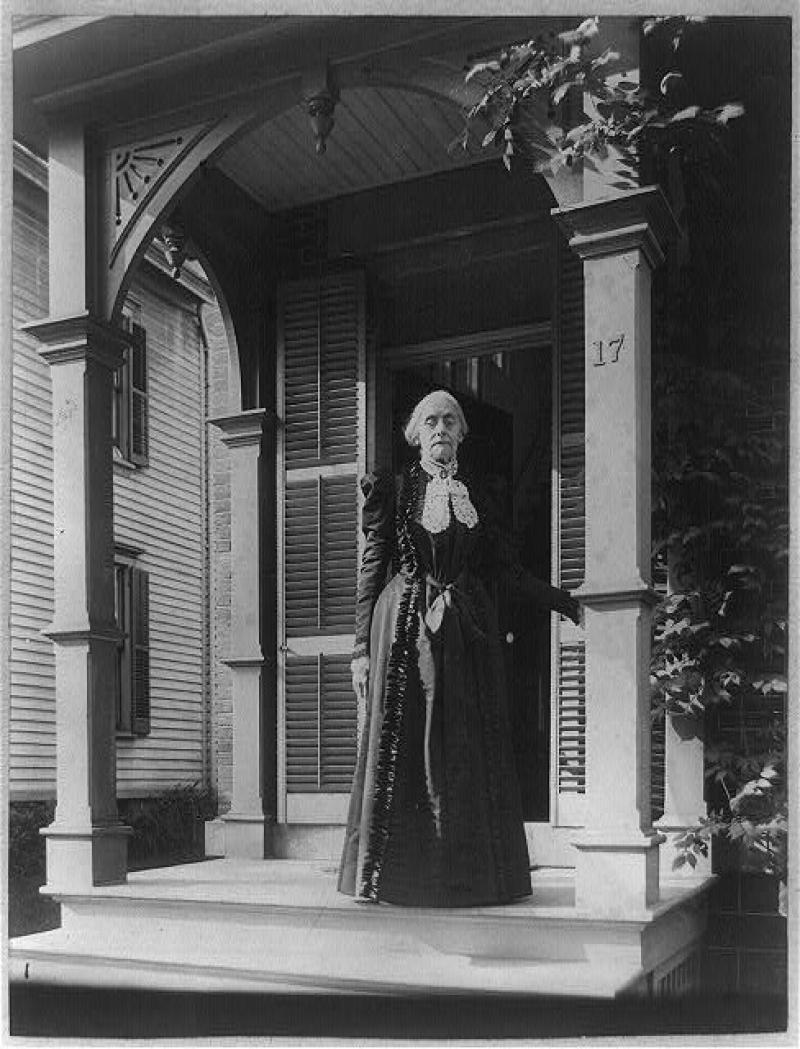

Susan B. Anthony

Although she died in 1906 and did not get to see her dream of women’s suffrage come true, Susan B. Anthony was a staunch and unrelenting supporter of women’s rights who worked tirelessly throughout her life to secure women the right to vote. She was highly intelligent and learned to read and write at age three. Raised a Quaker, Miss Anthony taught for a time at a Quaker seminary. Her discovery that the male teachers at her school earned higher pay than she earned for equal work inspired her to join the women’s rights movement. Later, an introduction to Elizabeth Cady Stanton further solidified her beliefs in women’s equality to men, and she dedicated her life to ensuring women’s civil rights. Miss Anthony believed that the wording of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave women the right to vote. To test her theory, she cast a vote in the 1872 presidential election. She was arrested, found guilty, and ordered to pay a $100 fine. She refused to pay and the court never pressed her to do so. Miss Anthony co-authored the first four volumes of the six-volume History of Woman Suffrage.

Women's Suffrage

National Women's Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was founded by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in 1869. That same year, Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The differences separating the two organizations were largely political. In 1890, the suffragists agreed to merge the two organizations to create the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Miss Anthony served as president of NAWSA from 1892 to 1900.

Women’s rights activists promoted suffrage as a way to expand the peace and harmony of the ideal home into the public realm. Sentimentality, however, was not a motivating factor. Instead, it was women’s legitimate claim to a decisive influence in the public sphere. Women’s work in settlement houses showed their ability to succeed in partially refocusing local government from business priorities to those that affected the health and welfare of ordinary families and communities.

First page of a letter from Susan B. Anthony to Indiana Republican Congressman Thomas McLelland Browne. Miss Anthony and several other women appeared before Congress in the days following the National Woman Suffrage Association’s Sixteenth Annual Washington Convention in March 1884. The women testified in support of a Sixteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution giving women the right to vote. Mr. Browne contributed to a statement in support of women’s suffrage that was read into the Congressional Record on April 24, 1884. Here Miss Anthony asks Mr. Browne for 1,000 copies of his remarks for distribution to the NWSA’s “members and friends.”

Women's Suffrage

Alice Paul

Women’s rights activist and DAR member Alice Paul was born in New Jersey in 1885. Very determined and highly intelligent, she held multiple degrees including a law degree and a Ph.D. She got an early start in her work for women’s rights, often attending suffrage meetings with her mother. In 1912, she joined NAWSA and was appointed Chairman of the organization’s Congressional Committee in Washington. Her activities initially consisted of strategic planning and fundraising. In 1913, Miss Paul and Lucy Burns broke from NAWSA and founded the National Woman’s Party (NWP) in order to fight for suffrage on the national level. The National American Woman Suffrage Association was focused mainly on obtaining suffrage at the state level while the NWP prioritized the passage of a constitutional amendment ensuring women’s suffrage throughout the country.